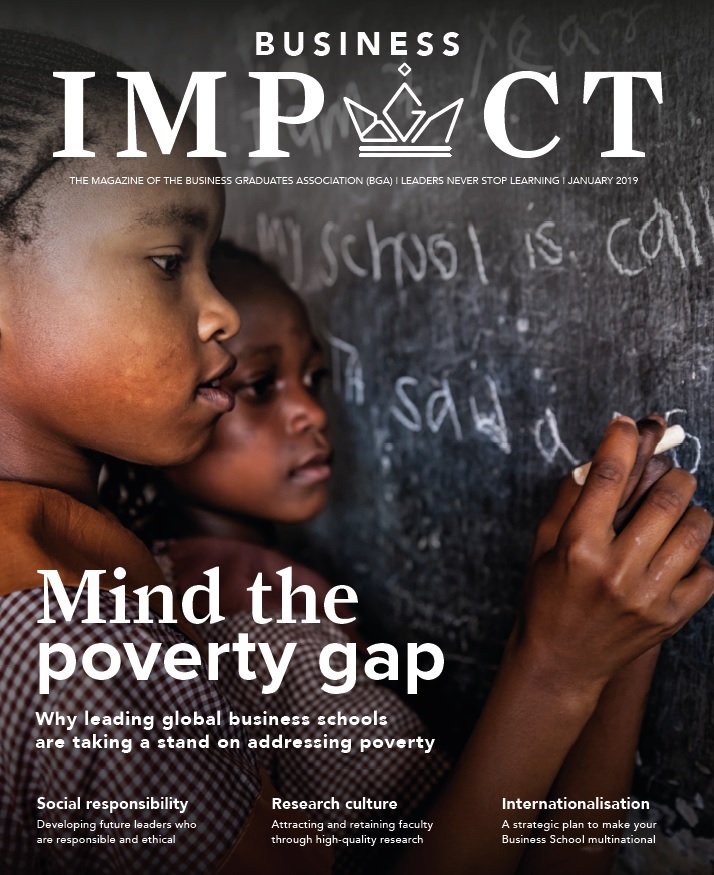

Andrew Main Wilson, CEO of the Business Graduates Association, launches Business Impact and outlines the mission and vision of the organisation

Thank you for taking the time to read Business Impact, our very first edition of the magazine which will discuss many of the issues that form the DNA of the biggest ever brand launch in our 52-year history – the Business Graduates Association.

We were originally founded in 1967 as the Business Graduates Association, before rebranding as AMBA – the Association of MBAs – in 1987, to focus more specifically on accrediting the world’s leading MBA and masters in general management Business School programmes, while also providing membership to AMBA Schools’ students and graduates.

Now, in 2019, we are relaunching this powerful brand name, which will stand out in a business education market full of difficult-to-remember brand name acronyms.

Our vision is very clear. BGA will champion the crucial importance of lifelong learning, selecting Business Schools as members who clearly demonstrate a passion for practical, entrepreneurial business education and an evident commitment to social responsibility and sustainability, across all their programme modules.

BGA will focus on providing membership, validation and accreditation across the entire programme portfolios of high-quality Business Schools. We will also offer free individual BGA membership to the students and alumni

of our BGA Schools.

Geographically, we will encourage membership from some of the world’s most sophisticated Business Schools, through to inspirational Business Schools in some of the world’s poorest countries, who can demonstrate admirable evidence in making a real difference to the future of their countries’ economies.

I have been very fortunate in interviewing some of the world’s greatest business and political leaders, from Bill Gates to Lady Thatcher, to Archbishop Desmond Tutu. They all share at least one common belief: the best way to increase fair wealth distribution and improve the quality of people’s lives worldwide, is through better education. Ultimately in life, whether a country is capitalist or communist, a democracy or a dictatorship, business funds society. So better business education for all is right at the forefront of improving our world.

This vision is the driving force behind BGA’s launch. We look forward to welcoming you to the BGA family and making a real difference worldwide to the education of our current and future business leaders.