Business isn’t capitalising on the benefits trust can bring, say HBS Professor, Sandra Sucher, and HBS Research Associate, Shalene Gupta. However, management students must know how trust relates to power and how leaders must govern themselves to keep it.

Leaders have powers other people don’t. They get to decide (or lead a process of deciding) what products or services a company will offer, how many people to employ and what kinds of jobs they will have, which suppliers to partner with, and even how to interpret laws and regulations. On the flip side, this also means leaders have to make difficult decisions that may mean causing harm in order to preserve the greater good. One senior executive told us that, ‘the fair decisions are easy. My job is to make the difficult decisions.’

Leaders have the responsibility of decision-making, which also means, in order to keep this authority, they must be trusted.

‘Trust’ refers to our ability to be vulnerable to an organisation, or a person, that may have power over us. For example, customers are vulnerable to an organisation because they have no window into how a product or service is created. They must trust that the product or service will work as it is supposed to, and that it is ethically created. Similarly, when employees agree to work for an organisation, they are trusting that they will not be abused and that they will have a reasonable amount of job security.

Trust and team performance

Research shows that teams who trust their leaders perform better. In a study of National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) basketball teams in the US, researchers found that trust in leadership was more important to winning than trust in one’s teammates. Teams that trusted their coaches won 7% more of their games than teams that didn’t. In addition, the team with the highest trust in its coach won the national championship, while the team with the lowest trust in their coach only won 10% of their games. As one player commented: ‘Once we developed trust in Coach___, the progress we made increased tremendously because we were no longer asking questions or were apprehensive. Instead, we were buying in and believing that if we worked our hardest, we were going to get there.’

The importance of building trust translates to a company’s bottom line as well. In a 2002 study of Holiday Inns, 6,500 employees rated their trust in their managers on a scale from 1 to 5. An increase in trust of 1/8th of a point was correlated with a 2.5% increase in revenues. At a macro level, this all scales up: a 1997 study of 29 market economies showed that a 10% increase in trust in the population correlated with a 0.8% increase in GDP.

However, as a community, business isn’t capitalising on the benefits trust can bring. According to the 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer, CEO credibility is at an all-time low in several countries, including Japan at 18% and France at 23% (in terms of the proportion of people who rate a CEO as a very or extremely credible source of information about a company) making the challenge for CEOs even more critical as they try to manage today’s issues.

Earning trust

Because leaders are responsible for decision-making, they must earn trust differently than organisations. Followers want first to know that a leader has earned their power legitimately, and second that they will use it well. They rely on their leader to make difficult decisions with compassion and fairness.

A leader who is not trusted won’t hold on to their position for long. Notable instances of this include the case of Boeing, a company that has suffered a major scandal where the CEO is later dismissed, and Harvey Weinstein, who was ousted after his multiple abuses were uncovered.

The American philosopher, John Rawls, calls that first act of earning trust by acquiring power legitimately at the beginning of a leader’s tenure (or the first exposure that you might have with her in her role) ‘originating consent’. There is then what he calls ‘joining consent’ – the fact that people continuously assess whether they want to keep trusting a leader with power.

Even if you come to your role through the right process, people still want to know on what basis you were selected. In democratic societies, we recognise the result of an election by consenting to allow the winning candidate to assume the job of mayor, governor, or president as our leader. In corporations, the process is less visible: boards of directors appoint CEOs, who we in turn consent to allow us to lead our organisations.

The process of building trust does not end when a leader first acquires power. It’s a status that is always being reassessed through joining consent. Trust needs to be earned over and over, throughout time.

However, leaders face an uphill battle when it comes to joining consent. The very qualities that cause you to earn people’s trust in the first place are easily destroyed by acquiring power. Business students need to be aware that part of retaining trust in the workplace involves governing yourself to resist the heady side-effects power can create, which paradoxically causes leaders to lose trust. The lexicon of business history is filled with stories of CEOs like Travis Kalanick, who created large companies and then got ousted due to losing touch with the public. But why does this happen?

The paradox of power

Dacher Keltner, a Professor of Psychology who heads up the University of California, Berkeley Social Interaction Lab has, for decades, studied power, which he defines as ‘one’s capacity to alter another person’s condition or state of mind by providing or withholding resources… or administering punishments.’ In his book, The Power Paradox (2016) Keltner describes his research and that of other leading scholars of power.

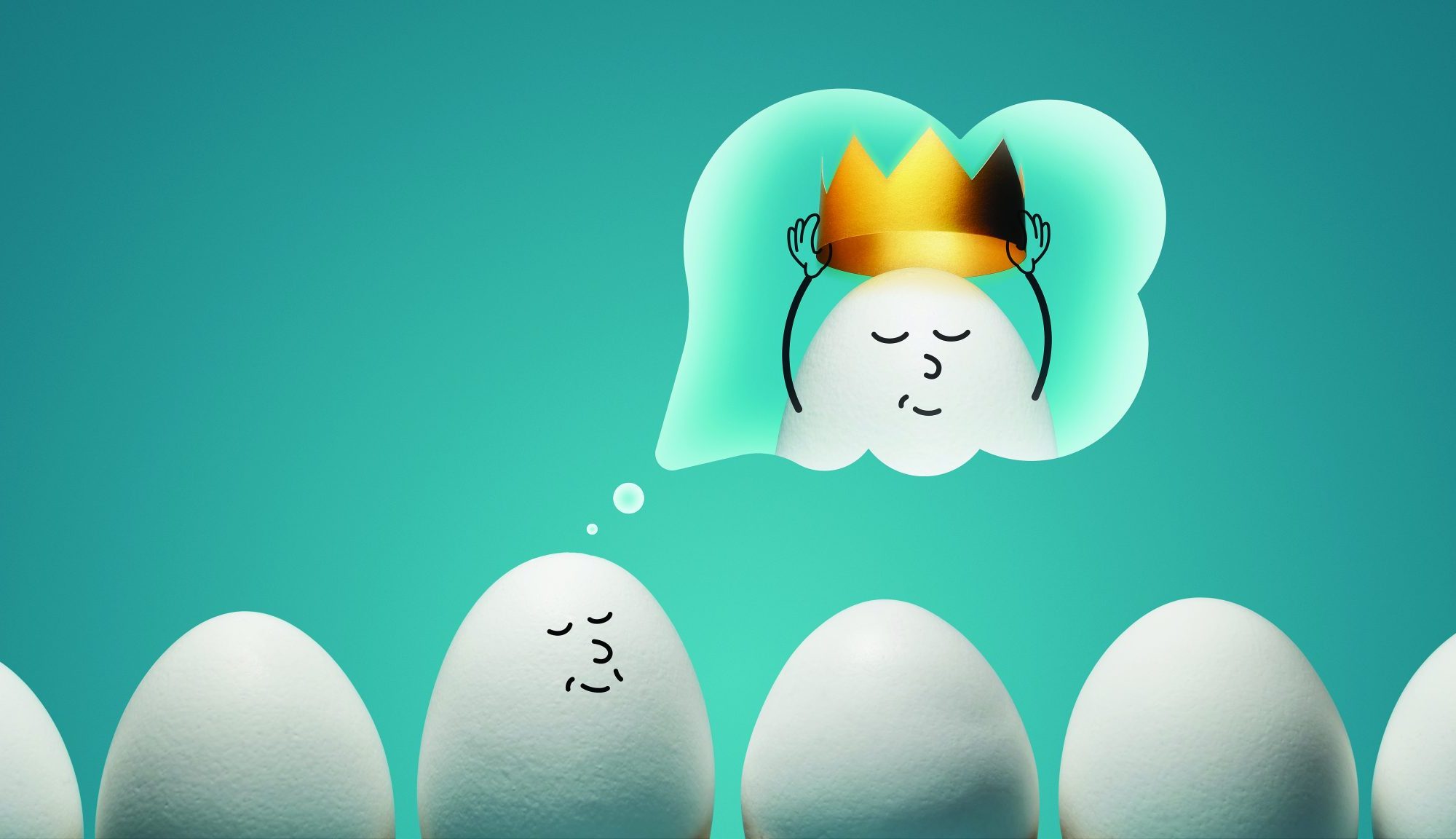

Power is a paradox in the following sense: the very behaviours that lead others to trust you with a position of power are (or can be) horribly transformed (think Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde) into behaviours that are the opposite of what people esteemed in you before. For instance, leaders often gain their power because of their willingness to listen to others, but once attaining it, they frequently downplay or even refuse to listen to dissenting voices. That is because being in a position of power affects both the way you see yourself and how others perceive you and the way you act.

Now, the second half of this paradox is not exactly news. There’s a reason why you have probably heard some version of the quote: ‘Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely’ – the famous opinion of the British historian, Lord Acton.

Let’s start with the first half of the paradox and Keltner’s description of the behaviours that lead others to trust you with a position of power. In this view, the road to earning and maintaining power is paved by caring actions that show focus on others. Groups create leaders. They ‘give power to those who advance the greater good, construct reputations that determine the capacity to influence, reward those who advance the greater good with status and esteem, and punish those who undermine the greater good with gossip.’ Keltner’s leaders demonstrate empathy, they give to others, and they show gratitude.

Characteristics of those who rise to power

Keltner conducted the research that first introduced him to these ideas 20 years ago. He wanted to understand why some people rise to power in a group, while others don’t. He began by designing a natural state experiment that would allow him to interact with participants as they went about their daily lives. He got permission to study the students who lived together in one hall within a first-year dormitory at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, a public university with a heterogeneous student body.

At the beginning of the year, he met students and asked them to rate the amount of influence each person living in the dorm held. Students also completed a questionnaire that asked them to assess the extent to which their own personalities were defined by five social tendencies – a group that psychologists refer to as the ‘Big Five’: kindness, enthusiasm (reaching out to others) focus on shared goals, calmness, and openness to others’ ideas and feelings. He returned in the middle of the academic year, and then at the end, asking students to rate the power held by each of their dorm-mates each time.

He tallied the power ratings given to each student. As early as two weeks into the year, some students already had more perceived power than others. His study also found that each student’s power fluctuated throughout the year. He found that those who rose to power had the most enthusiasm, and that the other Big Five traits also mattered.

Researchers replicated these results across 70 other studies, finding that the people who rose to power had all the Big Five personality traits. The studies were in settings as varied as hospitals, financial firms, manufacturing facilities, schools, and the military. This is overwhelming evidence that if you want to get power, you need to be someone who values others, who cares about the greater good, and who can help a group succeed.

The reason why Keltner’s book is called The Power Paradox, however, is that he later describe how the actions that might lead one to be chosen to have power can disappear under the neurological and psychological effects that being in a position of power can have on individuals. Keltner calls power a ‘dopamine high’. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that is released in our brains when we expect a reward. Keltner found that when people feel more powerful, they get dopamine highs. However, this makes them less aware of the risks associated with an action.

Perspective-taking and priming

This transformation from a focus on others to a focus on yourself is also a concern of Adam Galinsky, Professor of Leadership and Ethics at Columbia Business School, who is a renowned social psychologist. He and some colleagues conducted a deceptively easy-looking experiment to illustrate one of the worst effects of power on individuals, which is how it interferes with a person’s ability to take the perspective of others. A key component of empathy, perspective-taking, is the proverbial ability to walk in another person’s shoes, which means being able to see, feel, and imagine how someone else experiences the world.

However, if you literally can’t put yourself in someone else’s shoes, you can’t take their perspective into account. In Galinsky’s study of 57 undergraduates, he divided the students into ‘high-power’ and ‘low-power’ groups. Students in the high-power group were asked to write about a personal incident when they had power. In the low-power group, students wrote about a personal situation in which another person had power over them.

The students were then taken into a separate room and given a series of tasks: high-power participants were asked to allocate seven lottery tickets to themselves and another participant; low-power participants were asked to guess how many of the seven lottery tickets they would receive from another participant. Students were then given the following instructions: Task 1: with your dominant hand, as quickly as you can, snap your fingers five times. Task 2: with your dominant hand, as quickly as you can, draw a capital ‘E’ on your forehead with the marker provided.

Here is the amazing thing that happened. The participants in the high-power position wrote the letter E on their foreheads as if they were reading it themselves, which meant that the E would be backwards from the perspective of someone looking at them and trying to read it. And the participants in the low-power position wrote the letter so that a person looking at them would be able to read it easily. In other words, they wrote it considering the perspective of the other person, whereas the high-power group wrote it from their own perspective.

The experimental process used by Galinsky is called ‘priming’. It refers to the common and well-validated research technique that finds giving individuals tasks, like writing about a personal experience, will put them in a frame of mind to think of themselves in a particular way, in this case, as either a person of high power or someone with low power. So, just by being primed to think of yourself as high-power, you look at the world from your own perspective.

Preparing leaders for an internal battle

CEOs like Travis Kalanick from Uber (he of the toxic culture, never-ending scandals, and bad-boy fame) and Tony Hayward from BP after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (Mr ‘I’d like my life back’) are first-rate examples of what leadership looks like under conditions of power-laced self-focus, an inability to empathise, and indifference to harm imposed on others.

What this comes down to is that leaders at any level in an organisation, or even in their personal life, must be prepared for the internal battle that awaits. On one side is the focus on others and the good of the group – the actions and beliefs that enable people to gain power and the respect and admiration of others. On the other side is the well-documented finding that being in a leadership role will pull you towards a focus on yourself and replace attention to others with an inability to care, understand or even be curious about the conditions of other people or groups, except those who serve your interests.

Describe, analyse and judge: notes on teaching trust in leadership

I’ve [Sandra J Sucher] taught at Harvard Business School for 23 years, including courses on moral leadership, and leadership and corporate accountability. Trust is a skill and therefore when teaching it, it’s important to use examples instead of lectures.

In the classroom, I draw on a mixture of cases (I recommend Dave Cote at Honeywell to illustrate a trusted leader balancing different stakeholder needs: ‘Honeywell and the Great Recession (A)’ and ‘Honeywell and the Great Recession: The Economic Recovery (B)’) and examples from real life and great literature to stimulate discussions (William Langewiesche’s American Ground (2002) is a fabulous example of how a group earned originating consent,for example).

Then using a line of rigorous questioning, I get students to put themselves in a leader’s position. First, we start with observation; I call that step, ‘Describe’. What is the incident that’s happened? What are the leadership challenges? Then we take it deeper; I call that step, ‘Analyse’. Why did it happen? What factors contributed to the present? What do we know and what don’t we know? And finally, I have the students assess and debate the right course of action; I call that step, ‘Judge’. The reality is that in the midst of a crisis or a scandal it’s difficult to know what to do and sometimes there are no clear answers, just tough choices. Students often come into class hoping for right answers – what I hope to give them is a process for thinking through difficult dilemmas.

Sandra J Sucher (left) is a Professor of Management Practice at Harvard Business School, where she has taught for the last 20 years. At Harvard, Sucher has studied how organisations can change and improve while retaining stakeholder trust and the vital role that leaders can play in the process. She is also an advisor to the Edelman Trust Barometer.

Shalene Gupta (right) is a Research Associate at Harvard Business School. She is a former Fortune reporter, writing about diversity in Silicon Valley, big data, and smart cities, before which she worked at the US Department of Treasury and had a Fulbright grant in Malaysia.

Sandra J Sucher and Shalene Gupta are the authors of The Power of Trust: How Companies Build It, Lose It, Regain It (PublicAffairs, 2021).

This article is taken from Business Impact’s print magazine (edition: August-October 2021).I