What traits do you need to be a ‘sustainable leader’? Alison Watson, Head of the School of Leadership and Management at Arden University, looks at qualities to embrace and develop, and outlines why businesses will need them

Our next generation of leaders are going to be under intense pressure to incorporate sustainable practices into everything they do. They will need to ensure that businesses around the globe are contributing to the social, environmental and economic issues impacting our planet. This article considers the skills that business graduates will need to develop to ensure they can become the sustainable leaders of the future.

Changing consumer demands require adaptation

Brands across a wide variety of sectors and fields are placing a huge focus on sustainability right now – and with good reason. With the effects of climate change becoming ever more prominent and a rising public awareness around the pitfalls of some of the elements of western life we take for granted, such as fast fashion and unnecessary food waste, many consumers are looking to buy goods and services from businesses that operate in ethical and sustainable ways.

In 2021, sustainability has become an issue that is impossible to ignore and businesses, in turn, have become compelled to act. The leaders of today must adapt quickly to meet this consumer demand – their businesses risk being left behind if they are unable to do so.

Meanwhile, the development of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals has driven many businesses to think about how they can incorporate environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) goals within their organisations to become cleaner, greener and more ethically minded.

But what about the leaders of tomorrow? How will these changes impact them?

Leadership the world needs

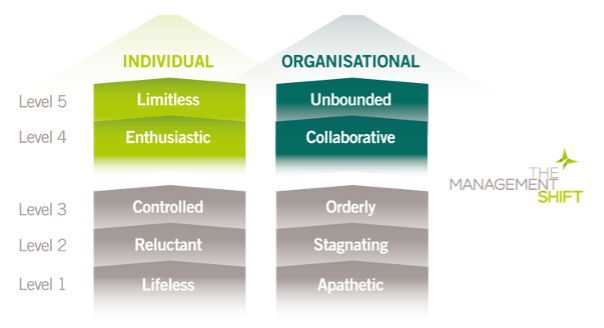

The leaders of tomorrow will be expected to be holistic in their approach and make decisions based on sound moral and ethical principles. They’ll need to empower their teams and be visionaries about the ways in which we can revolutionise business to maximise sustainable and ethical practices.

Put simply, they must become people who will drive change and help create a better world by addressing the core social, environmental and economic issues affecting our planet.

But what core traits will business graduates of today, and therefore the leaders of tomorrow, need to develop to be successful sustainable leaders?

Long-term-thinking visionaries

In business, it’s all too easy to get caught up in the now – and that’s understandable when you consider the multiple pressures our business leaders are under as part of their everyday roles. CEOs are typically working in fast-paced environments and often don’t have the short-term stability to make sound, long-term decisions on projects which won’t bring about an assured uplift in profits.

The sustainable leaders of tomorrow, however, will need to be able to align those short-term business objectives with longer-term, strategic plans that consider objectives related to economic health, the environment, people and society.

At their core, sustainable leaders should have a comprehensive worldview which contemplates and understands humanity’s place as part of a global ecosystem. They will need to consider how we can minimise our impact on the world around us and ensure we are responsible stewards of the planet we call home.

Once they’ve identified their longer-term objectives, these individuals will need to be able to lead and influence others. Leaders will need to take others along on their journey in generating a commitment necessary to ensure everyone works towards a common set of objectives and goals.

As individuals with a strong moral compass, sustainable leaders must also focus on making decisions that are rooted in moral and ethical principles. They should also be able to back these decisions to the hilt – being responsible and accountable for the decisions they make and the outcomes that follow them.

Seekers of collaboration

The best sustainable leaders are expert collaborators who seek involvement in networks that can broaden their understanding of the business landscape and the way it impacts our world.

By engaging with other leaders from a range of specialisms and sectors, leaders can broaden their horizons and continually inform their developing worldview. It can help to adjust their perspectives and enable them to build strong, long-lasting relationships with key stakeholders. These networks will also reinforce an understanding of people across various cultures and backgrounds, allowing leaders to become keen advocates of diversity.

At the heart of this, sustainable leaders must have a deep understanding of people. They need to know how to empower and get the best from their teams while having a deep emotional and social intelligence which enables them to gauge the impact of their decisions on the people around them.

Effective educators

By its very nature, being a sustainable leader means embarking on a period of change within an organisation. The best leaders take others along on this journey with them, not only by influencing and inspiring, but also by educating their teams so that they understand the reasons behind the decisions being made.

When it comes to managing their people, sustainable leaders must focus on coaching and mentoring, rather than dishing out commands and giving direct instruction. They should empower their teams to learn for themselves and hone their abilities so that they are able to address core challenges themselves – exploring, learning, and devising actions which can help them to address the common challenges they face.

All of this will help ensure that they develop their business’ culture in line with the objectives they have set out, embedding sustainability within the corporate culture and giving their organisation the best possible chance of supporting the world’s sustainability agenda.

Alison Watson is Head of School of Leadership and Management at Arden University. Alison has a wealth of experience in business and management having worked for a number of large retailers as an operations and project manager. Her recent research interests focus on inclusion and encouraging wider access to higher education.