You must login/create an account to view this content

Exploring the future of globalisation

You must login/create an account to view this content

Leaders never stop learning

Andrew Main Wilson, CEO of the Business Graduates Association, launches Business Impact and outlines the mission and vision of the organisation

Thank you for taking the time to read Business Impact, our very first edition of the magazine which will discuss many of the issues that form the DNA of the biggest ever brand launch in our 52-year history – the Business Graduates Association.

We were originally founded in 1967 as the Business Graduates Association, before rebranding as AMBA – the Association of MBAs – in 1987, to focus more specifically on accrediting the world’s leading MBA and masters in general management Business School programmes, while also providing membership to AMBA Schools’ students and graduates.

Now, in 2019, we are relaunching this powerful brand name, which will stand out in a business education market full of difficult-to-remember brand name acronyms.

Our vision is very clear. BGA will champion the crucial importance of lifelong learning, selecting Business Schools as members who clearly demonstrate a passion for practical, entrepreneurial business education and an evident commitment to social responsibility and sustainability, across all their programme modules.

BGA will focus on providing membership, validation and accreditation across the entire programme portfolios of high-quality Business Schools. We will also offer free individual BGA membership to the students and alumni

of our BGA Schools.

Geographically, we will encourage membership from some of the world’s most sophisticated Business Schools, through to inspirational Business Schools in some of the world’s poorest countries, who can demonstrate admirable evidence in making a real difference to the future of their countries’ economies.

I have been very fortunate in interviewing some of the world’s greatest business and political leaders, from Bill Gates to Lady Thatcher, to Archbishop Desmond Tutu. They all share at least one common belief: the best way to increase fair wealth distribution and improve the quality of people’s lives worldwide, is through better education. Ultimately in life, whether a country is capitalist or communist, a democracy or a dictatorship, business funds society. So better business education for all is right at the forefront of improving our world.

This vision is the driving force behind BGA’s launch. We look forward to welcoming you to the BGA family and making a real difference worldwide to the education of our current and future business leaders.

A strategy for business school internationalisation

A strategy for business school internationalisation

Topic selection:

In an increasingly globalised market, the world’s top business schools are taking a strategic approach to internationalisation by developing goals and actions designed to advance their institutional brands and missions. While the context and character of these strategies and their deployment differ, the schools we will refer to as ‘high-performing international business schools’ possess some shared attributes largely responsible for enabling their strategies.

Before exploring these attributes, let’s look at some of the different manifestations of internationalisation that are emerging across the business school landscape.

Directions and manifestations

First, internationalisation strategies are generally directed towards a combination of goals. The recent EAIE Barometer Study indicates that preparing students for a globalised world, improving the quality of education and research, and enhancing institutional competiveness stand out as the most-commonly cited.

Second, internationalisation strategies within the business school world tend to be fairly holistic. Not all schools are pursuing comprehensive internationalisation strategies – where internationalisation efforts are maximised and integrated across all domains of the institution’s work – but most are framing strategies that are fairly broad in their nature.

International accreditations are likely to promote breadth and depth in internationalisation and to promote international quality standards in teaching and research. Business school leaders tend also to see the scope for and benefits of internationalisation across different domains and the tendency for progress in one area to support progress in another.

A strong and continued focus on student mobility and recruitment sits at the heart of most institutional strategies but other priorities around faculty diversity and mobility, research, and curriculum internationalisation also tend to shape institutional action. Many schools are seeking to integrate a digital approach and are looking at digital platform strategies.

Third, business school internationalisation has become synonymous with business school mobility and cross-border operations. Notwithstanding the popularity of e-business strategies, we see evidence of large-scale investments by business schools outside of their home market either through direct investment (campuses and representative offices) or through strategic partnerships that function to facilitate the delivery of programmes at offshore locations.

These can range from short executive education formats to longer degree-granting provisions. They involve arrangements based on hosting, delegation and franchise, sometimes in combination with digital strategies. This exportation of capabilities and/or programmes tends to be one of the distinguishing factors for the most aggressively international schools. In the Financial Times 2018 listing of the world’s Top 30 European business schools, six (or 20%) are identified as multi-locational, including the likes of INSEAD and ESCP Europe.

Internationalisation, like any business process, requires a series of judgements. Even if the orthodoxy is for business schools to take an holistic approach to internationalisation, there is still ample scope to pursue a strategy of focused differentiation driven by institutional mission and vision.

Some business schools have sought to build their brands and identities around a particular reputation for research or programme excellence. Some have emerged as international specialists in such fields as entrepreneurship, leadership development, or digital learning. Equally, internationalisation as an evolutionary and often stage-based process does not mean that business schools should move at one pace or at an accelerated one.

Indeed, many business schools have regretted their haste in major investments abroad and/or in striking international partnerships without mission consonance or due diligence. Finally, strategic partnerships and networks have become central to the internationalisation project and mission, supporting the quality focus, breadth and dynamism we see as characterising business school internationalisation as a phenomenon.

From trends to attributes

Whatever the differences in the substance of what they do or in the pace and sequence of internationalisation efforts, schools are reliant upon a number of attributes that ensure the conception, development and sustainability of their internationalisation strategies.

If we isolate the case of high-performing international business schools (HPIBS) and look at their DNA, we identify seven key attributes, which we bring together in our 7-C framework:

1. Clarity

This first attribute provides the cornerstone for successful international development, regardless of its form or scale. The ‘why‘

that guides these developmental imperatives is addressed in the mission and vision of

these high-performing schools therefore enabling a clear and coherent framework for decision-making and resource-allocation processes. Explicit alignment with the

school’s identity and positioning is fundamental for legitimacy and support from both internal and external stakeholders.

While the mission and vision drive internationalisation, a well-articulated strategy provides the road map. The clarity of that strategy and the shared narrative it engenders within the institution are key factors of success.

2. Capital

HPIBS’ performance and competitiveness is significantly influenced by intangible assets or ‘intellectual capital’. Critical here are expert knowledge and competencies (human capital), the firm’s internal organisation and innovation systems (structural capital), and its ability to engage with and work with key stakeholders (relational capital). This resource-based view of the Business School clearly highlights organisational theory, which draws attention to the nature of intangible resources and co-ordination within the organisation. Clearly, it is unimaginable that an HPIBS exhibiting research leadership or research excellence could occupy such a position without the intellectual capital of its faculty. However, that capital is unlikely to be sufficient in itself without an organisational ability and propensity to both foster and exploit that intellectual capacity.

The leading international business schools also enjoy brand or reputational capital, which emerges as a result of their contribution and impact. This is generally manifest in high levels of brand recognition, strong rankings placement, and/or accreditations. All of these may be seen as a proxy measure of quality but the industry attaches huge significance to these yardsticks.

3. Configuration

HPIBS are not simply competing internationally but are configured internationally. They have assets, networks and operations that extend beyond their domestic market. Configuration issues concern where in the world each activity in the value chain (e.g. marketing and programme delivery) is performed, and where human and physical assets are located and linked.

Unlike the domestic business school, this value chain has an international quality with some degree of geographic dispersal of both assets and activity. Linked to this are management-control and co-ordination issues concerning the co-ordination of each activity when it is done in more than one place. This means that they must have management models and structures in place to support and execute an advanced internationalisation strategy. Some HPIBS have opted to configure as multi-campus networks, others more as

hub-and-spoke operations. Some have attached international partners to their organisation to deliver their programmes without internalising specific offshore activities. The bottom line however is that these schools are set up internationally (they are not merely selling their courses into an international marketplace) and this is supporting their mission and progress.

4. Connections

Configuration issues relate closely to the partnership models that business schools put in place to support and execute their strategies. The literature on internationalisation highlights the extent and benefits of international partnering with fellow schools, delivery partners, agents, and business firms. The continuing priorities of business schools are such that partnerships are typically at the core of the internationalisation process. HPIBS typically take a strategic approach to partnership development and management. They build and develop strong partner networks that have a bilateral and multilateral dimension. Productive links with other schools (for exchange of students, research and double/joint diplomas) are balanced by strategic engagements in multi-party networks and special interest groups linked closely to operational regions and strategic priorities.

5. Culture

HPIBS also have an organisational culture that drives and supports internationalisation. This is rooted in the values, beliefs, and assumptions held by organisational members, including its leaders. What is at issue here is the value set of the institution and their organisational climate. Most profess a strong desire to prepare global leaders or to influence global business. Most promote, celebrate and harness diversity. This is manifest in mission and value statements. This desire must be matched however by effective organisational processes that support the international aspect or focus of the mission. In essence, HPIBS are underpinned by an international culture that is evident in their people, beliefs, and ways of working. Sometimes attached to this are artefacts and symbols that reflect that international identity and aspiration.

In the case of ESCP Europe, an advanced model of internationalisation is reflected not simply in a multi-campus structure and rotational degree programming, but also in an international leadership team and the existence of pan-European institutes and departments. These are a product of a culture rooted in European identity and the values of diversity and plurality.

6. Community

HPIBS invest strongly in community. These schools both nurture and leverage a wide variety of stakeholders ranging from students to alumni to corporate partners to diplomatic connections. They bring these stakeholders together around a strong sense of identity and purpose and they do so at the international level not purely in their domestic arena. International community groups, alumni chapters and high geographic dispersal rates for graduates are typical traits. For example, Grenoble Ecole de Management (GEM) organises an Alumni Leaders’ Summit each year, pulling in alumni from all corners of the globe to discuss current affairs at GEM and to monitor how the programmes continue to impact even years after graduation.

The importance of this attribute lies in its very capacity to serve both a prospective and a safety function for an institution seeking to deploy internationally. Through its ‘community’, and a balance of use of and reward for this community, a School develops its networks exponentially and its capacity outside of its home market.

7. Curriculum

Schools wishing to internationalise fully must also be prepared to drill down into programme content and ensure the range of skills and knowledge that will serve as enablers for graduates to develop personally and professionally in a globalised world. Student satisfaction is increasingly related to the international toolkit they are provided with over the course of their studies. This kit is composed of content (intercultural theory, international case studies, global perspectives), exposure (multinational classrooms, language tuition, foreign faculty) and experience (curriculum-based study aboard, international internships and projects, study trips and industry visits).

If HPIBS are associated with these seven attributes, what is clear is that they have not all emerged quickly or easily. Becoming international in process terms and/or as a stamp of international quality or standing is not quick or easy.

Business school leaders and teams should make choices that are realistic and mission-driven. Lessons can be learned from HPIBS but not all schools are destined to replicate their models or strategies.

Professor Simon Mercado is Campus Dean/Director for ESCP Europe Business School, London.

Julie Perrin-Halot is Associate Dean/Director of Quality and Strategic Planning Grenoble Ecole de Management.

Read more Business Impact articles related to collaboration:

How higher education can forge successful partnerships with industry

A willingness to collaborate is the critical factor for employers and institutions, according to Oxford Business College’s Phillip Stone, as he outlines some dos and don’ts for successful partnerships

The value of collaboration between higher education and industry

What are the advantages and challenges of educational institutions working in partnership with industry? Oxford Business College’s Phillip Stone offers an overview that takes in the changing skillsets demanded by employers and strategies for schools to follow

The new normal of collaboration: the view from Latin America

The deans of the School of Management and Social Sciences at Universidad ORT Uruguay, the Universidad de San Andrés Business School in Argentina and Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV) EAESP in Brazil discuss new possibilities for Business Schools to partner with others and widen their reach

Want your business school to feature in

Business Impact?

For questions about editorial opportunities, please contact:

Tim Banerjee Dhoul

Content Editor

Business Impact

Share this page with your colleagues

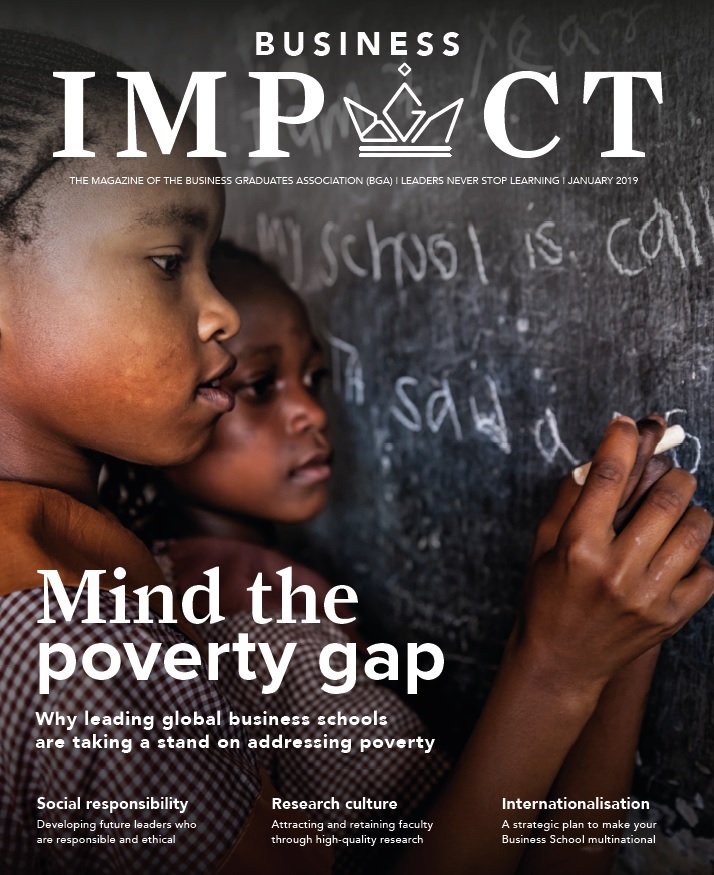

Mind the poverty gap: how the most progressive business schools in the world are trying to help close it

Mind the poverty gap: how the most progressive business schools in the world are trying to help close it

The United Nations reports that 783 million people live below the international poverty line of $1.90USD a day. This means that more than one in every 10 people on this planet struggle to access the most basic human needs such as clean water, healthcare and education.

Many millions more live just above this ‘line’, struggling to make ends meet, but without hope of building a more prosperous future.

For these individuals, upward social mobility is not a realistic aspiration. Instead, excessively poor working conditions and anxiety around surviving on their limited resources dictate their lives. They cannot afford to invest

money or time to obtain the skills they need to exploit opportunities that may arise, and even when they can, their local economy does not enable them to prosper.

As a global business school community, we should reach out beyond the walls of our institutions and address the most important issues facing our society, especially when these relate so closely to why we do business: to provide a living for ourselves and those around us in a global marketplace.

The economy is not serving the poorest people, so business schools have a duty to understand how business can work for society and influence those who can implement management changes for the better. In this same respect, business schools have a duty to also train and teach those who cannot afford to enrol onto their programmes.

The most progressive business schools are responding to this challenge by opening themselves up to helping those with fewer opportunities and researching ways in which doing business can help those with less.

As part of BGA’s mission, we want to highlight how business schools around the world are working to alleviate poverty, conducting research that covers case studies of three business schools initially, and highlights their work – and its impact – to boost opportunities to some of the poorest in society.

This work does not come without tangible challenges, such as financial capacity, the school’s scope of influence, and systematic barriers within the economy. But our case studies highlight the progress these projects have made in helping those who are disadvantaged work towards a more prosperous future.

This BGA research is just the start of the Business Graduates Association’s goal to understand the business school’s contribution to society.

Local community of social entrepreneurs

Ndileka Zantsi, Programme Co-ordinator at the University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business (UCT GSB) outlines its work in the community to produce social entrepreneurs of the future.

The UCT GSB opened a new teaching and research site – the Solution Space Hub – in Philippi, an impoverished community, located in the heart of Cape Town, South Africa, in 2016. The hub is an ecosystem for early-stage startups and a research and development platform for corporates to experiment with emerging business models, with a tangible connection to the wider community.

This year, the GSB Solution Space, in partnership with the Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship, has incubated two cohorts of 10 entrepreneurs enrolled on the Impact Venture Incubation Programme (IVIP) for a three-month period to help them build viable and scalable innovation-driven companies. We emphasise social impact when selecting projects to support, ranging from personal and industry training to products and services, which are accessible and affordable to those in less affluent neighbourhoods in and around Cape Town. Examples of current projects of entrepreneurs enrolled onto the programme include initiatives setting up a low-cost open-air cinema; designing an intuitive learning app for secondary school children, and training young people to narrate and edit their own stories.

The first month typically consists of exploring the customer base for the entrepreneur’s products or services, the second month is about developing the products or services to make them desirable to the consumer, and the third teaches the entrepreneur about making the products or services viable. After the three months, we provide post-programme support to ensure that entrepreneurs can continue to have access to a range of resources such as the co-working space, advisory services, practical learning clinics, weekly check-ins, staff advisors, and a community of peers who can learn and grow together.

Programme facilitators include current MBA students and UCT GSB alumni who teach on a pro bono basis.

The programme also pairs entrepreneurs with mentors, who are relevant industry experts, including our alumni. We have learnt from experience that the best time for the pairings is during months two or three. We are mindful of the entrepreneur’s background, and flexible around the timeframes for integrating entrepreneurs with their mentors.

In addition to providing education, advice and guidance, the programme also assists entrepreneurs with physical resources, where possible, to get their enterprise off the ground. This includes free access to a computer lab, office space, meeting rooms and a conferencing venue for running workshops or events. There have been substantial challenges we have had to overcome along the way, including issues we were not able to anticipate. Something we did not foresee was the emotional support we would need to

provide entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs here often experience tough situations in their personal lives, which, along with starting a business, can lead to mental health issues.

As a programme, we did not have the means to provide this support, but have been able to reach out to the university’s psychology department which now provides the support and advice pro bono.

We also provide food and transport for those entrepreneurs who may not have the financial means to afford these in order to attend the requisite sessions and spend time during the day interacting and learning from one another. This is something we did not budget for initially, but we deemed it necessary in order to guarantee the presence of the entrepreneurs for the

full three-month period.

The benefits of the programme are wide-ranging. Perhaps most importantly, it has made being an entrepreneur desirable for a lot more people in the community.

It is seen as a pathway that is achievable, one in which people can be successful and do good for others in society. As such, it has increased the reputation of entrepreneurship.

In the most recent cohort there were 61 applications for 15 spaces. But the areas of personal development are also significant. People have been able to develop transferable skills, scale their businesses, and provide employment for others in the community.

ESPAE’s academic research into how supply chains can be improved in Ecuadorian farming

Jorge Rodriguez, Assistant Professor at ESPAE Graduate School of Management, describes how his research into training smallholder farmers and urban micro-retailers about how they can operate more efficiently could benefit both low-income producers and consumers.

Companies across the globe want to increase sales in developing markets – including Ecuador and other countries in Latin America – but they face problems in doing this effectively due to high transaction costs, poor infrastructure and institutional voids such as appropriate financial systems. In Ecuador, for example, 80% of farmers are small scale. This means they often do not have the economies of scale to invest in efficient technology, are physically and digitally distant from both the manufacturers and consumers, and do not have access to the latest training methods to improve their production and distribution potential.

As part of my research role at ESPAE, which focuses on CSR, sustainability and stakeholder management, I am evaluating how a particular education training programme, funded by the Ecuadorian Agriculture Ministry, can make a measurable difference to the ways in which low-production farmers distribute their profits.

We are hoping that this training programme will benefit the farmers and their families. The research project tests whether the training programmes enhance farmers’ productivity and multi-dimensional poverty. The evaluation finds that training programmes enhance the productivity and reduce poverty of smallholder farmers, yet the scale of the programme is low. In this regard, the research informs policymakers on the appropriate mechanism to foster agricultural development.

The training covers a broad spectrum of issues, including informing farmers about ways in which they can overcome crop-yield problems, integrate better with suppliers and ensure they connect better and become more responsive to market demands. It is hard for these farmers to be better integrated into value chains, however, because they lack access to the formal economy, banking and medical services, education, and technology such as the internet or mobile phones. So, as a Business School, we see helping these farmers as a strategic priority. It is the right thing to do for these producers, who are currently on the fringes of economic innovation, yet are central to the workings of a large sector of the economy and low-income consumers.

My research project does not come without substantial challenges. For example, I am unable to identify participating farmers, meaning that I need to control for areas which do and do not receive the training, rather than specific farms.

There are also wider challenges around how we can get governments and firms to work better together to ensure that the training, if deemed successful, is rolled out more widely. As such, there are communication issues associated with ensuring that the findings of my

research are exposed to influential individuals, and that these findings are

acted on.

In this respect, as a business school community, we require greater collaboration both in terms of how we explore and evaluate business solutions, and how we communicate our findings to legislators and the marketplace.

Business schools need to approach local media in order to shout about the importance of our findings. We need to engage local authorities, stakeholders, and invite firms to talk about the topic, in order to have further tangible impact. A central issue we have is that business school staff are incentivised in terms of teaching objectives, faculty goals and cohort intakes, but are not challenged enough to help and support organisations and people directly.

The sector needs to rise to this by up-skilling academics to become mainstream communicators of their work.

In the future, there also needs to be an increase in engagement between professors and students on this topic, because together we can make an impact around reducing poverty in our world. Farmers need to form co-operatives to consolidate its integration into value chains. Yet, there are few people with administrative skills in rural areas.

I think business school can contribute to changing this reality. We can work with students on live cases to enhance the administrative skills of farmers’ co-operatives, and rural organisations.

Leadership and management programme for future leaders

Dr Ijeoma Nwagwu, Manager of the Sustainability Centre at Lagos Business School, talks about her school’s programme to enhance the management skills of future leaders working in NGOs.

I work as part of the management faculty in the areas of strategy and sustainability, so I am interested in engaging on topics of responsible management and economic development. I manage Lagos Business School’s Sustainability centre.

The activity areas for the centre include research, capacity building and stakeholder engagement. Our activities focus on the themes of corporate sustainability (helping businesses become a force for good), social entrepreneurship and sustainable infrastructure.

We deliver a leadership and management programme that we co-created with the Ford Foundation to develop a pipeline of young leaders. The programme aims to bring young leaders from the NGO and social enterprise ecosystem into the Business School to work out innovative ways to tackle poverty through their work. We enrol up to 100 leaders annually and they come from organisations that focus on a range of sustainable development issues such as gender, agriculture, health and children, and the environment. This programme focuses on equipping young leaders with practical knowledge of business fundamentals, social innovation and leadership effectiveness in an increasingly complex world.

The whole idea behind the programme is leadership development for young people in NGOs, who have an opportunity to put those skills into practice to advance impact in the social sector. Our purpose is to develop 100 leaders a year, providing them with a platform to hone their leadership skills through experiential learning and to develop networks with others in the space to facilitate peer-to-peer learning. I believe this engagement in the journey of learning to be invaluable, as at the heart of poverty is a lack of knowledge.

The role of the business school is to contribute to knowledge generation and community building on issues around poverty.

From the teaching perspective, we need to make sure that young leaders understand their roles and are appropriately equipped to solve social problems. On the research and documentation side, our faculty is developing a handbook on NGO leadership and management in Africa.

The scope of the Lagos Business School’s work reaches beyond this programme. We are beginning to make a substantial impact with our work. What we know is that more than 40% of local adults are operating outside the formal financial system with negative consequences in their ability to save, manage life’s shocks through insurance, debt and other modern financial services. Therefore, the School has run a project on sustainable and inclusive digital financial services which, through research and advocacy, supports the financial sector with the necessary knowledge to build financial products that mirror the life experience of the poor. The ultimate aim is to provide poor people with greater access to improved financial services so they can thrive.

Although business schools can be seen as part of the establishment, we are not bound by stereotypes. Our vision of a business school is one that is inclusive, that connects people from different sectors and backgrounds, to develop socially responsible leaders to solve the most pressing social and economic problems.

The reality of our business school is that we bring people together from a range of industries, linking them to learn and grow for a better society.

This article originally appeared in the print edition (January 2019) of Business Impact, magazine of the Business Graduates Association (BGA).

Read more Business Impact articles related to corporate social responsibility:

Building a career with impact in CSR

Creative and ambitious people that can help businesses shape and deliver their CSR agendas are in demand, says Lakshmi Woodings. Discover what careers in CSR involve and the skills you’ll need to succeed

The principles of business ethics | How to adapt a responsible approach to management

As an impactful business school, adopting a responsible approach to business management is essential, for both the institution and its students alike. In this article,

The mutually beneficial pursuit of ethics and profits

Drawing on Apple and Patagonia as examples, The University of Law Business School’s Stuart Ailion considers the merits of strategies that combine ethical outlooks with profit making

Want your business school to feature in

Business Impact?

For questions about editorial opportunities, please contact:

Tim Banerjee Dhoul

Content Editor

Business Impact

Share this page with your colleagues

The CEO with a social conscience

The CEO with a social conscience

What are the biggest challenges facing a CEO, in this increasingly volatile, uncertain and complex world?

I think the change we’re seeing in the world today is unprecedented. Every aspect of the world is changing from the economic balance to the tools and technology we use to run our businesses. So the CEO of today has to have incredible strategic acuity, enormous resilience, agility, and flexibility, and then bring the rest of the organisation along with them. You can either see these times as incredibly exciting or very scary. Scary times call for leadership of a different kind to take us to a new place. That’s what we’re all going through today as CEOs.

What is your advice to business schools about the skills they need to be imparting to students, to provide graduates who are fit for purpose?

Business schools teach people to foster capitalism and these schools were created to enhance and keep capitalism alive. I think the shareholder value theory is the primary message that most business schools impart to their students; that is, shareholder value is paramount and creating value at all costs is what is taught. I’d go so far as to say that there is a focus on making money and if you have a legal problem, get somebody from the law school to solve it. If you have an environmental problem, get somebody from the environmental school to solve it. If everything fails, get somebody from the divinity school to pray for you…

However, things have to change because business cannot exist in a vacuum. Business cannot pass on costs to society and business cannot survive by just worrying about shareholders and not worrying about the communities and the societies in which they operate. We have to create a new form of capitalism that works for everyone and to do this, we need to re-tool Business Schools and students to realise that they’re not just going to graduate as money-making individuals, but have a purpose too. Students should graduate knowing that capitalism has a bigger role than just creating shareholder value in the short term.

Do you believe that a cohesive force of business graduates across the world could be a much bigger influence on society going forward?

In a way, everybody picks up the debris from what capitalism has done. If capitalism is really a force for good in society, you’re supposed to address the whole issue of inequality and make sure that money doesn’t just flow to the top, but flows to the whole pyramid. Governments are then stuck with the debris from capitalism gone wild.

If we really want business students to graduate as real citizens of the community, practising a new form of capitalism, they’ve got to understand that what they feel personally cannot be different from what they practise in their professional lives.

The best example somebody gave me was during the 2008 financial crisis. If every financial services firm’s capital was at stake, would they have taken the kind of risks that they took? But, if all of us feel vested interest in the companies for which we work, because they impact us personally, the companies would be different. We have to understand that companies are communities and we have to operate for the betterment of communities. To do this, student recruitment has to change, as does

how we develop students and how we judge success.

Salaries cannot be the only metric that assesses whether a school is good.

But unfortunately, that’s the only metric we have.

How can business schools teach students about issues of sustainability and responsible management. Should it be in their DNA?

It’s not in the DNA of the students because the intake is pretty diverse. Yet most business schools exist within a university ecosystem, where there are law schools, environmental schools and so on. So the questions to ask are: Do you break down the silos in the universities? Do you take a case and bring in people from the other schools to help you teach it? Why do you have to zip through a case? Why don’t you take one case and study all the facets of it? We’ve forgotten that business exists in a community and the university is a microcosm of that community.

Why shouldn’t business school professors say: ‘I can invite others in to give their perspectives’.

Also, we’re still trying to get these MBA students out in 18 months. We’re shortening the cycle when issues are more complex; for example, the role of social media in business. However, we don’t have the luxury to train novices for years.

What more do you believe should be done to attract women into business courses, or is the real problem higher up the tree as you start to move towards the boardroom?

The calibre of women in business schools is phenomenal, so clearly there’s leakage, because somewhere in middle management we’re losing them. I think when students want to get married and have children, the workload is not consistent with them doing all these jobs. You can say a lot of the millennials have equal partners who share in the workload, but equal partnering doesn’t mean the husband can give birth to the child. There are still roles the women play and somebody has to do the job disproportionally in child caring. Workplaces have not yet learned how to provide the kind of support to allow women to have a life and make a living. This change has to happen if we want to retain and promote women.

Another challenge we face is class stratification. We want people who step off the ‘track’ to come back. So we’ve started a trial programme to enable this. Also, if we want the best, we have to draw from the entire population, and the only way to do it is make the workplace an extension of the person’s life. For example, opening a day care centre here on campus, so parents, especially women, can tend to their children whenever necessary. More companies have to do this if we want women to come into the workforce.

How have you succeeded in combining the incredibly demanding roles of mother and CEO?

First of all, I have a very supportive husband, which helps. Second, having an extended family willing to help with the kids made a huge difference. They put their lives on hold to help us raise the kids.

PepsiCo itself is a great place because of the ecosystem that supported me. For example, even the CEO who I succeeded, Steve Reinemund, helped me pick up the kids when my husband was stuck in traffic; he’d say: ‘I’ll go pick up one and you go pick up the other’.

I’m very grateful to this company, for what it gave me and for what I’ve been able to do for the next generation of employees.

What advice would you give students on how to start a career overseas or, given the buoyancy of India as a business superpower, are they better off staying in India?

India has many issues, and needs a strong group of leaders to take it to the next level. Brain drain from India is not a good thing but these students have many more opportunities today than existed when I graduated. In my class, I was only one of five women. Today, 20%-40% of the class are women. Things have changed, so it behoves those kids to give back to the country for what the country has invested in them.

India has its share of problems and these business students can do wonders to help the country address these issues. If an army of graduates from the country’s top business schools cannot solve India’s problems, who is going to?

They live in the midst of these problems, and they should sit down and figure out how to address them.

What do you believe is the best way to ensure lifelong learning?

Business schools have a unique opportunity. Let’s say I graduated today from Yale School of Management, I’d love Yale to say that if I pay another

X thousand dollars, I can come back for a refresher programme for the next X number of years, to learn about the most important and current topics and have access to their online education to go deeper in those topics.

It’s a golden opportunity to keep that connection with alumni, and because the world is changing so profoundly, it is not possible for leaders to keep up with everything that’s going on.

But today, we have to keep learning. For example, I grew up in a generation where social media didn’t exist, but I have to learn about it because the young people who work here, and who live on these devices, are the people generating all the noise. On the other hand, you can’t take a 30-year-old and say run a $63bn USD company.

I think each of us also has to do our own learning, figuring out our curriculum and how we need to engage certain topics, we can’t just wait for others to give it to us. For example, today’s CEOs have to be foreign policy experts, understand issues in every country and the role of multilateral organisations, how NGOs think and behave, and understand really deep sustainability issues.

We have to keep learning. Expertise is a leaders’ goal. But we have to strive for this goal.

How would you like to see business graduates make an impact on our planet?

I’d say to each of them, bring your whole self to work and think of what you’re doing as having an impact on your community. Make it very personal and see if the business is doing the right thing by the ecosystem in which you live in. If it isn’t, work in the company to change the model.

The young people who are graduating now should make their voices heard to create change. Through this, we can actually reform capitalism to be a real force for good.

This article originally appeared in the print edition (January 2019) of Business Impact, magazine of the Business Graduates Association (BGA).

Read more Business Impact articles related to corporate social responsibility:

Building a career with impact in CSR

Creative and ambitious people that can help businesses shape and deliver their CSR agendas are in demand, says Lakshmi Woodings. Discover what careers in CSR involve and the skills you’ll need to succeed

The principles of business ethics | How to adapt a responsible approach to management

As an impactful business school, adopting a responsible approach to business management is essential, for both the institution and its students alike. In this article,

The mutually beneficial pursuit of ethics and profits

Drawing on Apple and Patagonia as examples, The University of Law Business School’s Stuart Ailion considers the merits of strategies that combine ethical outlooks with profit making

Want your business school to feature in

Business Impact?

For questions about editorial opportunities, please contact:

Tim Banerjee Dhoul

Content Editor

Business Impact