France’s Emlyon Business School aims to develop leaders that are able to adapt, anticipate, and transform. Executive President and Dean, Isabelle Huault, spoke to David Woods-Hale about its ambitious strategic plan

You’ve been in the role of Executive President and Dean at Emlyon Business School for over a year now. Can you share some highlights?

I was appointed Executive President and Dean in September 2020 and my assumption of duty was not ordinary, given this period of great restrictions and uncertainty surrounding Covid-19. Not being able to meet physically with the School’s teachers and staff, or with the students, alumni, or partners of emlyon, was difficult, but it still proved to be a great learning experience. I was able to observe and measure the teams’ commitment to the School, the courage of the students who faced this crisis – and who are determined to continue to adapt as the situation evolves – and I experienced the support of our partners in such a complex context.

Thankfully, the situation has calmed down, and energy and excitement are alive again on our campuses. Over the past year, we have also built a new gender-balanced, high-level team, which is complete and ready to implement our strategic plan: ‘Confluences 2025’.

Do you think the Business School community has been fast enough to innovate during the pandemic?

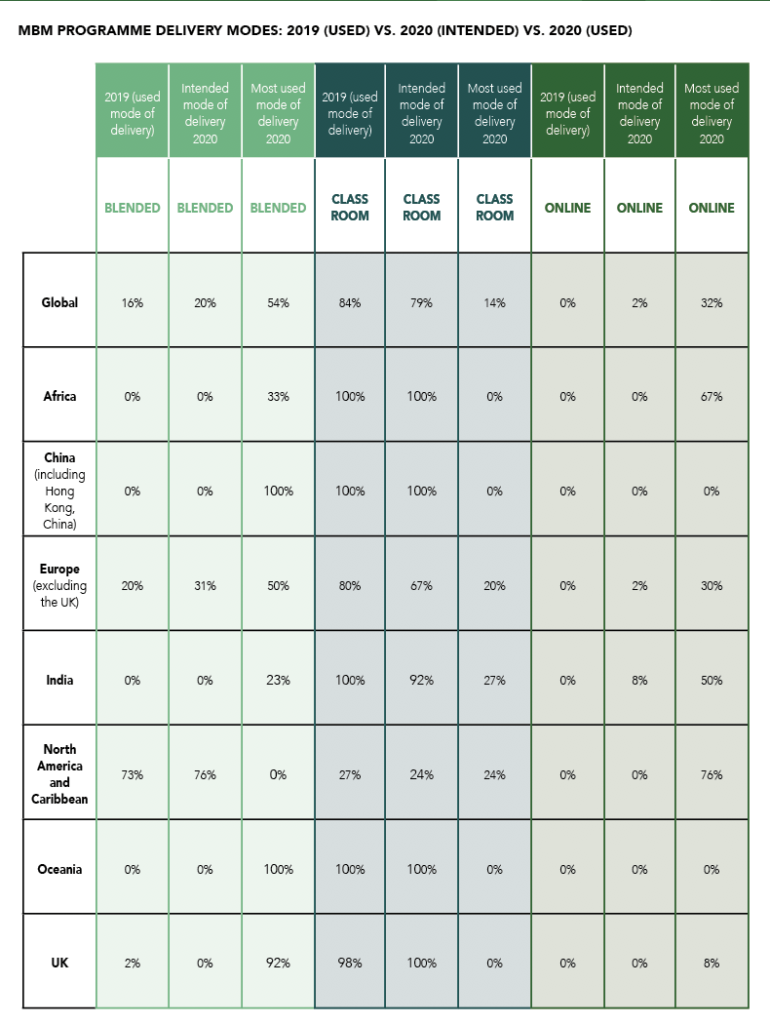

Covid-19 has accelerated digital innovation. We had already begun the digitalisation process of training sessions before the crisis hit, so once restrictions were put in place, emlyon Business School was ready. Both our professors and students were already familiar with the tools. Stimulated by the emergency, the School immediately improved its digitalisation process, and turned the crisis situation into an opportunity to innovate in our pedagogy, course delivery methods, and knowledge assessments. For some courses, both professors and students felt it brought more value to the programme. For example, it enabled them to devote less time to travelling while still allowing them to engage with experts from all over the world for a truly enriching educational experience, even from home.

However, after this period of isolation and distance, it has become very clear that elements such as a physical dimension, human contact, and in-person meetings are also essential components of higher education and research. We still need places to discuss, share and collaborate.

What are the next steps for you as a leader and for the School?

With our newly appointed leadership team and the support of the supervisory board, we’ve launched an ambitious strategic plan entitled ‘Confluences 2025’. Our goal is to become one of the leading global business universities in Europe according to three main strategic priorities: commitment to social and environmental issues, academic excellence through hybridisation, and networked internationalisation.

First, as CSR forms the guiding thread for all the School’s training programmes, the skills repository of all training programmes will be reviewed in line with the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To promote social inclusion, emlyon is launching a proactive policy of equal opportunities, scholarships and the development of apprenticeship training. The School is also set to consolidate the scientific quality of both the faculty and its research output by recruiting 10 new teacher-researchers in various disciplines each year until 2025.

To reinforce the hybridisation of its programmes, emlyon will sign numerous partnerships with renowned higher education institutions in the fields of art, design, social sciences, and engineering, both in France and in other countries. Our international expansion will involve the development of our campuses abroad and 20 more double degrees with global institutions of excellence until 2025.

Finally, the Lyon Gerland campus will embody the best of this strategy and welcome the community of Emlyon in 2024.

What do you think sustainable leadership looks like?

At Emlyon, we train students to transform business models – becoming ‘business transformers’ – and to be social change makers who have an impact on their environment and organisations. We also encourage them to exercise an entrepreneurial or intrapreneurial mindset in the organisations in which they’re involved – whether these are a small companies, Cotation Assistée en Continu (CAC) 40 companies, or consulting firms.

Ultimately, our students will become leaders able to adapt, anticipate, and transform. In addition to being effective, these future decision-makers will be enlightened, responsible, aware of the social and moral consequences of their actions, and know how to combine efficiency, justice and sustainability.

The Bigger Than Us movie directed by Flore Vasseur is a good example of sustainable leadership, and it’s the backbone of the 2021-2022 year at Emlyon. This documentary was filmed all over the planet and it shows young people fighting for human rights, the climate, freedom of expression, social justice, and for access to food and education. Presented at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival, it has been previewed by the 3,650 newcomers enrolled in our programmes to put their ideas into action.

How important do you think sustainability is, and in what ways have Business Schools adapted this into their programmes?

Social and environmental issues are at the heart of our project. Our students are asking, ‘how do I find meaning in my career?’ This focus, and the pandemic, has led us to review our courses to see how we can help students answer this question.

We have started to revisit our training offer, and all of our teaching units, according to the UN’s SDGs. By the end of 2022, nearly 60% of our training offer will have been reviewed and, within two years, it will be 100%.

At emylon, our social and environmental commitment is already renowned.In the 2021 EMBA Financial Times ranking, emlyon is ranked fourth in the world and first in France in the criteria Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG). This is because we are deliberate about incorporating sustainability, corporate and social responsibility, and ethics within the executive MBA programme. Working with professors, we have developed a set of 35 competencies related to these topics, which are diffused into every course in the programme, and also link to the UN SDGs.

Our marketing course focuses on the ethics involved when marketing to children; our strategy course shows how companies can create sustainable business models, and our governance and compliance course shares best practices from companies relating to these topics. In addition, we have a number of courses such as ‘business for positive impact’ and ‘corporate and social responsibility delivered’ which focus exclusively on topics around corporate social responsibility, and incorporate real-world company and NGO challenges. Our goal is to develop responsible leaders, ready to contribute to improving business, society, and the environment.

Given the climate emergency, do you think Business Schools have a role in helping communities to respond to, and recover from, natural disasters?

Having a positive impact on the planet is a very ambitious goal which mobilises our entire faculty and all programme departments. The School’s objective is to hone students’ skills so that they can meet social and environmental challenges. For example, today we cannot deliver a marketing course without addressing the issue of responsible consumption, or programmed obsolescence, which definitely have consequences on pollution and global warming. We plan to create an ‘SDGs Inside’ label to emphasise the focus on issues surrounding social sustainability, ethics and ecological transition.

Business Schools have to be exemplars in their day-to-day operations to inspire students. On our French campuses, we will realise [and measure] our carbon footprint by December 2021. Energy performance plans have already been signed with services providers for our Paris and Lyon campuses in order to promote energy savings. We have also implemented a waste-sorting policy and moved to ‘zero single-use plastics’ with the elimination of food consumption plastics (cups, cutlery, and so on). A zero-waste box was distributed to students in all our programmes (reusable cup, box and bamboo cutlery, etc.).

Our new campus, due to open in 2024, will be exemplary in terms of environmental responsibility. A 9,000m² landscape park will allow us to restore nature and biodiversity on a site which was, up until now, a brown-field site. The bioclimatic building design will allow to optimise energy consumption; the building is going for the French HQE™ Excellent certification, and the BREEAM ‘very good’ rating.

In July 2021, Emlyon became a certified B corporation (B Corp). Could you tell us more about this?

We reached a major milestone last summer: Emlyon Business School became a B corp on 26 July, after its supervisory board voted to approve the change.

The School’s mission, now defined in its mission statement, is: ‘To provide life-long training and support to enlightened individuals able to transform organisations, for a more inclusive and sustainable society’.

It’s a structuring and unifying project that was initiated upon my arrival in September 2020. We worked on it with all of our stakeholders: students, faculty, staff members, partners, and of course, our supervisory board. It’s the result of a participatory process that has enabled us to formulate our social and environmental objectives clearly. It’s the starting point for the School’s strong, long-term commitment.

The School is making SDG 10-Reduced Inequalities a core focus and launching a mandatory ‘climate action’ course as part of the MSc in Management – Grande Ecole programme. How might this impact your MBA curricula?

This year, we offered our new students a ‘back-to-school’ under the sign of CSR, dedicated, specifically, to the UN’s SDG number 10, which aims to reduce inequalities between and within countries. On this occasion, the new cohort was able to attend an inaugural conference with a prestigious speaker, Pascal Canfin, President of the Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety at the European Parliament, which focused attention on to the climate issue.

In September 2021, we also launched the compulsory course ‘Act for the climate’ in the Grande École Programme (MiM). This introductory cycle is planned over 10 weeks at the rate of one seminar per week. The first five sessions will allow students to acquire all the fundamentals to understand the context and the principles of climate emergency. Over the following five sessions, students will learn how to explain big issues to the different [decision-makers] and how these actors take or should take initiatives to act.

As a result of achieving B Corp status, the School has adapted its vision and goals. Could you tell us about these?

As required by the French law ‘Pacte’, the management of our project will be regularly monitored by an independent organisation. Our social and environmental engagement must flow through all of our activities. Using a precise grid, the audit company will be responsible for evaluating our actions and commitments. We would lose B corp status if we did not follow the ambitious objectives that we have set ourselves. This underlines the fact that the decision we have taken is obviously very [important to us].

What are the biggest challenges facing international Business Schools?

I guess the biggest challenge for international Business Schools is to educate our students to address significant new challenges in a changing world. The biodiversity and preservation of the planet are the main issues going forward. It requires the radical transformation of our programmes and of our research.

Learning trips have heavy carbon footprints, but it is not about questioning our global strategy, but rather avoiding short journeys to the other side of the world. We have reflected on this subject, particularly in terms of our MSc, and for scientific conferences. There is no question of giving up international openness; we consider that essential to the multicultural and learning experience of our students and members of Faculty, but to arbitrate on the question of mobility in a reasonable way.

Political, economic and social inequalities tend to generate extreme violence. Business Schools have to fight against discrimination and violence and promote openness and mutual respect. We have launched an online reporting platform, called ‘speak up’, where anyone can report instances of discrimination, sexism, or sexual violence. The platform is open to the school’s staff, and to Emlyon’s French and international students.

Developing diversity, and providing equal opportunities, is one of the main responsibilities of Business Schools. At emlyon, we support access to higher education for young people from underserved or priority education districts and rural areas, in association with volunteer students.

Over the past 15 years, in a number of middle schools, high schools and preparatory classes, we have implemented two systems aimed at lifting students’ self-censorship: tutoring and preparation sessions for oral examinations have helped high-school students to identify a wider range of career options, to think more ambitiously regarding their desired professional project, and, ultimately, to integrate successfully into the best Business Schools. More than 4,000 high-school students and 800 preparatory class students took advantage of these social programmes, and 180-plus students have joined the top eight Business Schools in France; 80 are at Emlyon.

What do you think differentiates Emlyon Business School in the business education ecosystem?

We value ‘management’ because we consider it to exist at the crossroads of a wide variety of disciplines. It fits into society and the economy in general, and is a cornerstone for other diverse disciplines such as engineering sciences, artificial intelligence, humanities and social sciences.

An open application process is integral to our other key value: entrepreneurial spirit. Beyond entrepreneurship, we instil and encourage a spirit of initiative through our on-demand programmes, our Makers’ labs and other world-class facilities, and through our commitment to empowering community life.

It is our early makers pedagogy – according to which we ‘learn to do and do to learn’ – that is our great differentiator. This real-world approach enables leaders to be equipped to face the challenges of both today and tomorrow.

These values were ultimately captured in our mission statement, and are what distinguish us as both a School and as a benefit corporation.

Do you feel optimistic about the future of business, Business Schools, and the economy?

Let’s stay positive. There will certainly be a decline in GDP both in France and internationally, but also growth prospects. New activities will continue to be created, while others have already grown around digital services, and some entrepreneurs may cease their current activities to invest in new ones. The coming months will cause worry, and that’s normal, but new opportunities are likely to appear too. For example, the Covid crisis has also led to a collective awareness about climate emergency and fostered global solidarity.

In this context, Business Schools have a role to play in developing knowledge that allows us to innovate, take action, reinvent, and develop. What is essential is to provide knowledge and skills that allow individuals to adapt throughout their professional lives. It’s about having both fundamental knowledge and soft skills – the vital interpersonal skills that we do not always possess inherently, but must learn.

And finally, it’s about having the capacity and skills to prepare and respond proactively to emerging models that do not currently exist. Let’s imagine them here and now.

Isabelle Huault became Executive President and Dean of Emlyon Business School in September 2020. She was President of Paris Dauphine-PSL from December 2016 to 2020, having been a Professor at the School since 2005.

This article is adapted from one which originally appeared in Ambition – the magazine of the Association of MBAs.