You must login/create an account to view this content

Exploring the principles and value of strategic corporate social responsibility

Exploring the principles and value of strategic corporate social responsibility

The global leadership responsibility imperative has firmly moved corporate social responsibility (CSR) to the forefront of the management agenda. Why is now the right time for you to launch your book Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility?

My book captures (and is designed to help lead) a major shift that is currently taking place. CSR has been here for a few decades, but there has been a lot of focus on corporate philanthropy and a narrow way of seeing CSR, not to mention ‘greenwashing’ [a form of spin in which PR or marketing is deceptively used to promote the perception that an organisation is environmentally friendly].

The focus has also been on how CSR serves business and shareholders, which is important, but it cannot continue to be the only reason to be more responsible.

The book emphasises the importance of strategic CSR, which is holistic and comprehensive, about being responsible in everything that we do, including core operations, and with everyone with whom we do business (namely all our stakeholders). It also incorporates a long-term approach instead of a short-term one. CSR cannot continue to be little more than a side show focusing on charity.

We face tremendous global challenges and business can play a vital role in helping address them through the power of strategic CSR.

How would you define strategic CSR?

I have used this definition of strategic CSR by Chandler: ‘The incorporation of an holistic CSR perspective within a firm’s strategic planning and core operations so that the firm is managed in the interest of a broad set of stakeholders to achieve maximum economic and social value over the medium to long term.’ This definition offers a broader view of corporate responsibility, one that is embedded in everything the firm does – from its strategic planning and core operations.

I also see strategic CSR as CSR that is aligned with what the company stands for and what it does best. Instead of ‘random acts of charity’, the company uses its knowledge, resources and capital to make a real difference. The only thing I would change in this definition is ‘maximum economic value’– maximising profit and growth at any cost is no longer viable. We can make profit, but not maximise profit at the expense of humanity and this planet.

Do you think sufficient numbers of business leaders around the world are putting CSR into their strategic agendas?

The business sector is like a huge ship moving slowly in the ocean. It is now shifting direction, but due to its size, it is not always easy to see. If we don’t shift – we will hit the iceberg. I strived in my book to focus on positive examples of corporate responsibility instead of on the more visible corporate social irresponsibility – not because I am naïve, but because I wanted the book to inspire others to follow these good examples.

As such, I focus on inspirational leaders, such as Paul Polman of Unilever, who, with his sustainable living plan, has shifted the entire focus of the company to sustainability, and leaders such as Indra Nooyi of PepsiCo, who leads performance with purpose. There is a shift: CSR is becoming an important part of the strategic agenda for many companies, instead of a charitable sideshow. Is it enough? Not just yet, but we are getting there.

CSR was previously considered something that could impact the bottom line if done properly. Do we need to move away from this and think strategically, yet altruistically, when it comes to CSR?

I am glad that CSR helps to impact the financial bottom line. It means that people care about these issues more than ever before when they buy from a company as consumers or work for it as employees. Research shows a strong relationship between being genuinely responsible and employee engagement and performance. Having said that, companies shouldn’t only lead CSR for this purpose.

There is a ‘catch 22’ here – if you only do good things to achieve employee engagement and consumer loyalty – it doesn’t work. Consumers, employees and other stakeholders can usually tell, even if not immediately, that CSR is not genuine. Usually, there will be some unethical behaviour involved. And greenwashing will lead not only to lack to trust in the company, but to lack of trust in CSR in general.

There is nothing worse than being unethical about your ethical behaviour.

So yes – you need to think strategically about CSR, work hard for real stakeholder integration, avoid shortcuts and above all – be genuine.

Do you feel enough is being done to embed the UN’s 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) into business strategy?

The SDGs are so important, not only because they aim to achieve remarkable goals, such as ending poverty and hunger by 2030, but also because they offer a great opportunity for humans to discuss what is important for us as a race and how we can achieve it together. The SDGs present an enormous task and challenge, and therefore require global and cross-sectorial collaboration like never before.

As I wrote in the European Financial Review, this is not only a challenge for business, but also a great opportunity to align strategy with something that matters to everyone. I see large multinational companies, as well as smaller ones, that choose to focus on several SDGs and take amazing and innovative actions to help achieve them.

There is work to be done to get more companies and stakeholders on board, but I have never seen so many companies aligned around shared goals as in the case of the SDGs.

What are some of the best ways to implement CSR strategies into an organisation, so employees take these initiatives on board, and so stakeholders, in turn, can see the organisation is making a difference?

If a company wants to adopt strategic CSR, it must integrate and involve all its stakeholders to do so. First, because it is an enormous task, and second, due to the definition and nature of strategic CSR. By definition, it requires working with a broad set of stakeholders and for CSR to be embedded in everything that we do – and you cannot do this with the executive leadership alone.

There are great ways to involve employees, consumers, shareholders and all other stakeholders in the company’s strategic CSR. Employees can be involved in corporate volunteering and sustainability, but they can also lead the strategic direction of the company’s CSR. In my book, I discuss employee-led CSR and provide some great examples of it. Companies involve their consumers, who show higher levels of consumer social responsibility than ever before, in their giving, volunteering and sustainable development.

You cannot do it alone, you shouldn’t do it alone, and involving your stakeholders is the only way to achieve holistic responsibility in everything that you do.

Should an organisation market its CSR? If so, how can it do it in a way that is ethical?

That’s a great question and the reason why I have included an entire chapter on CSR marketing. It was important for me to offer a book that outlines the theories, concepts and models on the one hand, but also the practical tools of CSR on the other. I did not see a chapter on CSR marketing in other CSR books, and decided to write one.

The chapter focuses on three aspects of CSR marketing: should we PR our CSR, ethical marketing, and social marketing. To answer your question – yes, we should market our CSR, because it is a good way to communicate with our stakeholders, inspire others and be held accountable for what we are doing. BUT – and this is a big ‘but’ – companies should only do it if their CSR efforts are holistic and genuine.

I give examples in the book of companies that were not genuine and holistic, and how CSR marketing backfired. It doesn’t mean that the company needs to be perfect – I don’t know a perfect company – but CSR needs to be holistic. You cannot do harm to people’s health and the planet in your core business and then market your corporate volunteering or company’s giving. It doesn’t work.

How would you define a responsible leader and what are the challenges they are facing today?

I don’t think we can talk about strategic CSR, let alone achieve it, without responsible leadership. I discuss concepts such as responsible, ethical, sustainable, servant, conscious, and transformational leadership in the book, as each of these concepts bring another important aspect of responsible leadership.

At the end of the chapter, I offer an holistic definition of responsible leaders that aligns with the one of strategic CSR: ‘People (in any position) with a strong purpose and a vision to better humanity, who incorporate an holistic CSR perspective within a firm’s strategic planning and core operations, work to meet the interests of a broad set of stakeholders, and strive to achieve maximum economic and social value over the medium to long term.

‘They do so based on a strong purpose and values, while being true to the self and with the aim to serve others. They share the leadership with others in the organisation in order to achieve these goals.’ This definition also emphasises that responsible leadership doesn’t have to come from the top – any employee can help lead social responsibility.

How important is it to measure the impact of CSR, and what are some of the best and innovative ways in which this can be done?

It is extremely important to measure the impact of CSR for several reasons. It provides constant benchmarking which can help the company improve its CSR; it increases accountability; it helps to communicate with and involve all stakeholders; and it assists in setting clear goals. Social impact assessment (which is processes of analysing, monitoring and managing the intended and unintended social consequences) also provides vital information that allows a company to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of its CSR compared to other companies; what it has done in the past and to what it could do in the future.

It therefore creates a pathway for improvement and a strong impact in the future. There are many ways of assessing social impact, from the basic logic model to social return on investment. What is important is to measure outputs and impact, not only inputs and outcomes, which is what most companies still do.

You reference management guru Peter Drucker in your writing. He said that in every social issue there is an opportunity. Do you believe there is an imperative for business schools to address societal problems?

Absolutely! As the shift is taking place in the business sector, the attention is also drawn to business schools and their role in developing business leaders who are responsible and ethical. There is a great opportunity for business schools to rise to the occasion and use their own resources, talent and capital to make a difference.

I have been conducting international studies together with the UN Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME), and the voice of millennial students all around the world is very clear: they expect their schools to deliver responsible management education and to help them lead responsible businesses.

I see business schools that are doing amazing things – from assisting refugees to helping to end poverty, and a genuine shift in mindset, leadership and curriculum. Analysing the mission statements of the Financial Times top 100 business schools, I found that 70% of them frame their mission around responsibility and impact. It is a great time to be an educator and a leader in this field.

Do you think MBAs have taken more of an interest in using their skills to create a more sustainable world over the past few years?

I don’t think so, I know so. These studies I have been doing with PRME on MBA students around the world demonstrate that the new generation of business students is very different to those that came before. There are many studies from the 1990s and 2000s showing business students to be less ethical and more corruptible than other students and that business education only made them more unethical. But this has changed. Our studies, and others, show that business students now care very much about sustainability and CSR and expect their business schools to deliver on this.

These studies received a lot of attention from the general media, and were mentioned by the New York Times, because they deliver a clear and different voice of the students. One of the most interesting findings was that one in five business students were willing to sacrifice 40% or more of their future salary to work for an employer exhibiting all aspects of CSR. I am very optimistic about the future of our world when I see what MBA students care about. I don’t think we should leave our problems to the next generation, but I know it will be a much better generation of business leaders than previous and current ones.

Debbie Haski-Leventhal is an Associate Professor of Management at Macquarie Graduate School of Management (MGSM), the Faculty Leader of Corporate Citizenship and the Director of Master of Social Entrepreneurship. As a scholar of CSR, Debbie initiated and led the MGSM CSR Partnership Network. Together with PRME, she conducts international studies on MBA students and their attitudes towards CSR and responsible management education. She has published over 100 papers on CSR, responsible management education and volunteerism, including more than 40 peer-reviewed articles in highly-ranked journals. Her book on Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility with a foreword by David Cooperrider was published in March 2018 by SAGE.

This article originally appeared in the print edition (January 2019) of Business Impact, magazine of the Business Graduates Association (BGA).

Read more Business Impact articles related to corporate social responsibility:

Building a career with impact in CSR

Creative and ambitious people that can help businesses shape and deliver their CSR agendas are in demand, says Lakshmi Woodings. Discover what careers in CSR involve and the skills you’ll need to succeed

The principles of business ethics | How to adapt a responsible approach to management

As an impactful business school, adopting a responsible approach to business management is essential, for both the institution and its students alike. In this article,

The mutually beneficial pursuit of ethics and profits

Drawing on Apple and Patagonia as examples, The University of Law Business School’s Stuart Ailion considers the merits of strategies that combine ethical outlooks with profit making

Want your business school to feature in

Business Impact?

For questions about editorial opportunities, please contact:

Tim Banerjee Dhoul

Content Editor

Business Impact

Share this page with your colleagues

Want your business school to feature in

Business Impact?

For questions about editorial opportunities, please contact:

Tim Banerjee Dhoul

Content Editor

Business Impact

Share this page with your colleagues

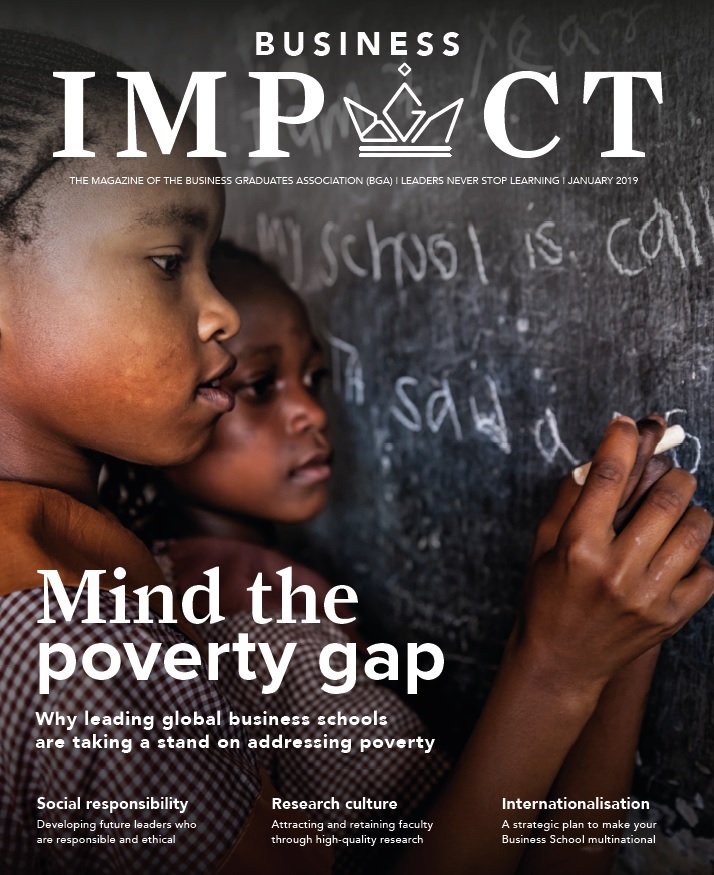

Mind the poverty gap: how the most progressive business schools in the world are trying to help close it

Mind the poverty gap: how the most progressive business schools in the world are trying to help close it

The United Nations reports that 783 million people live below the international poverty line of $1.90USD a day. This means that more than one in every 10 people on this planet struggle to access the most basic human needs such as clean water, healthcare and education.

Many millions more live just above this ‘line’, struggling to make ends meet, but without hope of building a more prosperous future.

For these individuals, upward social mobility is not a realistic aspiration. Instead, excessively poor working conditions and anxiety around surviving on their limited resources dictate their lives. They cannot afford to invest

money or time to obtain the skills they need to exploit opportunities that may arise, and even when they can, their local economy does not enable them to prosper.

As a global business school community, we should reach out beyond the walls of our institutions and address the most important issues facing our society, especially when these relate so closely to why we do business: to provide a living for ourselves and those around us in a global marketplace.

The economy is not serving the poorest people, so business schools have a duty to understand how business can work for society and influence those who can implement management changes for the better. In this same respect, business schools have a duty to also train and teach those who cannot afford to enrol onto their programmes.

The most progressive business schools are responding to this challenge by opening themselves up to helping those with fewer opportunities and researching ways in which doing business can help those with less.

As part of BGA’s mission, we want to highlight how business schools around the world are working to alleviate poverty, conducting research that covers case studies of three business schools initially, and highlights their work – and its impact – to boost opportunities to some of the poorest in society.

This work does not come without tangible challenges, such as financial capacity, the school’s scope of influence, and systematic barriers within the economy. But our case studies highlight the progress these projects have made in helping those who are disadvantaged work towards a more prosperous future.

This BGA research is just the start of the Business Graduates Association’s goal to understand the business school’s contribution to society.

Local community of social entrepreneurs

Ndileka Zantsi, Programme Co-ordinator at the University of Cape Town Graduate School of Business (UCT GSB) outlines its work in the community to produce social entrepreneurs of the future.

The UCT GSB opened a new teaching and research site – the Solution Space Hub – in Philippi, an impoverished community, located in the heart of Cape Town, South Africa, in 2016. The hub is an ecosystem for early-stage startups and a research and development platform for corporates to experiment with emerging business models, with a tangible connection to the wider community.

This year, the GSB Solution Space, in partnership with the Bertha Centre for Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship, has incubated two cohorts of 10 entrepreneurs enrolled on the Impact Venture Incubation Programme (IVIP) for a three-month period to help them build viable and scalable innovation-driven companies. We emphasise social impact when selecting projects to support, ranging from personal and industry training to products and services, which are accessible and affordable to those in less affluent neighbourhoods in and around Cape Town. Examples of current projects of entrepreneurs enrolled onto the programme include initiatives setting up a low-cost open-air cinema; designing an intuitive learning app for secondary school children, and training young people to narrate and edit their own stories.

The first month typically consists of exploring the customer base for the entrepreneur’s products or services, the second month is about developing the products or services to make them desirable to the consumer, and the third teaches the entrepreneur about making the products or services viable. After the three months, we provide post-programme support to ensure that entrepreneurs can continue to have access to a range of resources such as the co-working space, advisory services, practical learning clinics, weekly check-ins, staff advisors, and a community of peers who can learn and grow together.

Programme facilitators include current MBA students and UCT GSB alumni who teach on a pro bono basis.

The programme also pairs entrepreneurs with mentors, who are relevant industry experts, including our alumni. We have learnt from experience that the best time for the pairings is during months two or three. We are mindful of the entrepreneur’s background, and flexible around the timeframes for integrating entrepreneurs with their mentors.

In addition to providing education, advice and guidance, the programme also assists entrepreneurs with physical resources, where possible, to get their enterprise off the ground. This includes free access to a computer lab, office space, meeting rooms and a conferencing venue for running workshops or events. There have been substantial challenges we have had to overcome along the way, including issues we were not able to anticipate. Something we did not foresee was the emotional support we would need to

provide entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs here often experience tough situations in their personal lives, which, along with starting a business, can lead to mental health issues.

As a programme, we did not have the means to provide this support, but have been able to reach out to the university’s psychology department which now provides the support and advice pro bono.

We also provide food and transport for those entrepreneurs who may not have the financial means to afford these in order to attend the requisite sessions and spend time during the day interacting and learning from one another. This is something we did not budget for initially, but we deemed it necessary in order to guarantee the presence of the entrepreneurs for the

full three-month period.

The benefits of the programme are wide-ranging. Perhaps most importantly, it has made being an entrepreneur desirable for a lot more people in the community.

It is seen as a pathway that is achievable, one in which people can be successful and do good for others in society. As such, it has increased the reputation of entrepreneurship.

In the most recent cohort there were 61 applications for 15 spaces. But the areas of personal development are also significant. People have been able to develop transferable skills, scale their businesses, and provide employment for others in the community.

ESPAE’s academic research into how supply chains can be improved in Ecuadorian farming

Jorge Rodriguez, Assistant Professor at ESPAE Graduate School of Management, describes how his research into training smallholder farmers and urban micro-retailers about how they can operate more efficiently could benefit both low-income producers and consumers.

Companies across the globe want to increase sales in developing markets – including Ecuador and other countries in Latin America – but they face problems in doing this effectively due to high transaction costs, poor infrastructure and institutional voids such as appropriate financial systems. In Ecuador, for example, 80% of farmers are small scale. This means they often do not have the economies of scale to invest in efficient technology, are physically and digitally distant from both the manufacturers and consumers, and do not have access to the latest training methods to improve their production and distribution potential.

As part of my research role at ESPAE, which focuses on CSR, sustainability and stakeholder management, I am evaluating how a particular education training programme, funded by the Ecuadorian Agriculture Ministry, can make a measurable difference to the ways in which low-production farmers distribute their profits.

We are hoping that this training programme will benefit the farmers and their families. The research project tests whether the training programmes enhance farmers’ productivity and multi-dimensional poverty. The evaluation finds that training programmes enhance the productivity and reduce poverty of smallholder farmers, yet the scale of the programme is low. In this regard, the research informs policymakers on the appropriate mechanism to foster agricultural development.

The training covers a broad spectrum of issues, including informing farmers about ways in which they can overcome crop-yield problems, integrate better with suppliers and ensure they connect better and become more responsive to market demands. It is hard for these farmers to be better integrated into value chains, however, because they lack access to the formal economy, banking and medical services, education, and technology such as the internet or mobile phones. So, as a Business School, we see helping these farmers as a strategic priority. It is the right thing to do for these producers, who are currently on the fringes of economic innovation, yet are central to the workings of a large sector of the economy and low-income consumers.

My research project does not come without substantial challenges. For example, I am unable to identify participating farmers, meaning that I need to control for areas which do and do not receive the training, rather than specific farms.

There are also wider challenges around how we can get governments and firms to work better together to ensure that the training, if deemed successful, is rolled out more widely. As such, there are communication issues associated with ensuring that the findings of my

research are exposed to influential individuals, and that these findings are

acted on.

In this respect, as a business school community, we require greater collaboration both in terms of how we explore and evaluate business solutions, and how we communicate our findings to legislators and the marketplace.

Business schools need to approach local media in order to shout about the importance of our findings. We need to engage local authorities, stakeholders, and invite firms to talk about the topic, in order to have further tangible impact. A central issue we have is that business school staff are incentivised in terms of teaching objectives, faculty goals and cohort intakes, but are not challenged enough to help and support organisations and people directly.

The sector needs to rise to this by up-skilling academics to become mainstream communicators of their work.

In the future, there also needs to be an increase in engagement between professors and students on this topic, because together we can make an impact around reducing poverty in our world. Farmers need to form co-operatives to consolidate its integration into value chains. Yet, there are few people with administrative skills in rural areas.

I think business school can contribute to changing this reality. We can work with students on live cases to enhance the administrative skills of farmers’ co-operatives, and rural organisations.

Leadership and management programme for future leaders

Dr Ijeoma Nwagwu, Manager of the Sustainability Centre at Lagos Business School, talks about her school’s programme to enhance the management skills of future leaders working in NGOs.

I work as part of the management faculty in the areas of strategy and sustainability, so I am interested in engaging on topics of responsible management and economic development. I manage Lagos Business School’s Sustainability centre.

The activity areas for the centre include research, capacity building and stakeholder engagement. Our activities focus on the themes of corporate sustainability (helping businesses become a force for good), social entrepreneurship and sustainable infrastructure.

We deliver a leadership and management programme that we co-created with the Ford Foundation to develop a pipeline of young leaders. The programme aims to bring young leaders from the NGO and social enterprise ecosystem into the Business School to work out innovative ways to tackle poverty through their work. We enrol up to 100 leaders annually and they come from organisations that focus on a range of sustainable development issues such as gender, agriculture, health and children, and the environment. This programme focuses on equipping young leaders with practical knowledge of business fundamentals, social innovation and leadership effectiveness in an increasingly complex world.

The whole idea behind the programme is leadership development for young people in NGOs, who have an opportunity to put those skills into practice to advance impact in the social sector. Our purpose is to develop 100 leaders a year, providing them with a platform to hone their leadership skills through experiential learning and to develop networks with others in the space to facilitate peer-to-peer learning. I believe this engagement in the journey of learning to be invaluable, as at the heart of poverty is a lack of knowledge.

The role of the business school is to contribute to knowledge generation and community building on issues around poverty.

From the teaching perspective, we need to make sure that young leaders understand their roles and are appropriately equipped to solve social problems. On the research and documentation side, our faculty is developing a handbook on NGO leadership and management in Africa.

The scope of the Lagos Business School’s work reaches beyond this programme. We are beginning to make a substantial impact with our work. What we know is that more than 40% of local adults are operating outside the formal financial system with negative consequences in their ability to save, manage life’s shocks through insurance, debt and other modern financial services. Therefore, the School has run a project on sustainable and inclusive digital financial services which, through research and advocacy, supports the financial sector with the necessary knowledge to build financial products that mirror the life experience of the poor. The ultimate aim is to provide poor people with greater access to improved financial services so they can thrive.

Although business schools can be seen as part of the establishment, we are not bound by stereotypes. Our vision of a business school is one that is inclusive, that connects people from different sectors and backgrounds, to develop socially responsible leaders to solve the most pressing social and economic problems.

The reality of our business school is that we bring people together from a range of industries, linking them to learn and grow for a better society.

This article originally appeared in the print edition (January 2019) of Business Impact, magazine of the Business Graduates Association (BGA).

Read more Business Impact articles related to corporate social responsibility:

Building a career with impact in CSR

Creative and ambitious people that can help businesses shape and deliver their CSR agendas are in demand, says Lakshmi Woodings. Discover what careers in CSR involve and the skills you’ll need to succeed

The principles of business ethics | How to adapt a responsible approach to management

As an impactful business school, adopting a responsible approach to business management is essential, for both the institution and its students alike. In this article,

The mutually beneficial pursuit of ethics and profits

Drawing on Apple and Patagonia as examples, The University of Law Business School’s Stuart Ailion considers the merits of strategies that combine ethical outlooks with profit making

Want your business school to feature in

Business Impact?

For questions about editorial opportunities, please contact:

Tim Banerjee Dhoul

Content Editor

Business Impact

Share this page with your colleagues

The CEO with a social conscience

The CEO with a social conscience

What are the biggest challenges facing a CEO, in this increasingly volatile, uncertain and complex world?

I think the change we’re seeing in the world today is unprecedented. Every aspect of the world is changing from the economic balance to the tools and technology we use to run our businesses. So the CEO of today has to have incredible strategic acuity, enormous resilience, agility, and flexibility, and then bring the rest of the organisation along with them. You can either see these times as incredibly exciting or very scary. Scary times call for leadership of a different kind to take us to a new place. That’s what we’re all going through today as CEOs.

What is your advice to business schools about the skills they need to be imparting to students, to provide graduates who are fit for purpose?

Business schools teach people to foster capitalism and these schools were created to enhance and keep capitalism alive. I think the shareholder value theory is the primary message that most business schools impart to their students; that is, shareholder value is paramount and creating value at all costs is what is taught. I’d go so far as to say that there is a focus on making money and if you have a legal problem, get somebody from the law school to solve it. If you have an environmental problem, get somebody from the environmental school to solve it. If everything fails, get somebody from the divinity school to pray for you…

However, things have to change because business cannot exist in a vacuum. Business cannot pass on costs to society and business cannot survive by just worrying about shareholders and not worrying about the communities and the societies in which they operate. We have to create a new form of capitalism that works for everyone and to do this, we need to re-tool Business Schools and students to realise that they’re not just going to graduate as money-making individuals, but have a purpose too. Students should graduate knowing that capitalism has a bigger role than just creating shareholder value in the short term.

Do you believe that a cohesive force of business graduates across the world could be a much bigger influence on society going forward?

In a way, everybody picks up the debris from what capitalism has done. If capitalism is really a force for good in society, you’re supposed to address the whole issue of inequality and make sure that money doesn’t just flow to the top, but flows to the whole pyramid. Governments are then stuck with the debris from capitalism gone wild.

If we really want business students to graduate as real citizens of the community, practising a new form of capitalism, they’ve got to understand that what they feel personally cannot be different from what they practise in their professional lives.

The best example somebody gave me was during the 2008 financial crisis. If every financial services firm’s capital was at stake, would they have taken the kind of risks that they took? But, if all of us feel vested interest in the companies for which we work, because they impact us personally, the companies would be different. We have to understand that companies are communities and we have to operate for the betterment of communities. To do this, student recruitment has to change, as does

how we develop students and how we judge success.

Salaries cannot be the only metric that assesses whether a school is good.

But unfortunately, that’s the only metric we have.

How can business schools teach students about issues of sustainability and responsible management. Should it be in their DNA?

It’s not in the DNA of the students because the intake is pretty diverse. Yet most business schools exist within a university ecosystem, where there are law schools, environmental schools and so on. So the questions to ask are: Do you break down the silos in the universities? Do you take a case and bring in people from the other schools to help you teach it? Why do you have to zip through a case? Why don’t you take one case and study all the facets of it? We’ve forgotten that business exists in a community and the university is a microcosm of that community.

Why shouldn’t business school professors say: ‘I can invite others in to give their perspectives’.

Also, we’re still trying to get these MBA students out in 18 months. We’re shortening the cycle when issues are more complex; for example, the role of social media in business. However, we don’t have the luxury to train novices for years.

What more do you believe should be done to attract women into business courses, or is the real problem higher up the tree as you start to move towards the boardroom?

The calibre of women in business schools is phenomenal, so clearly there’s leakage, because somewhere in middle management we’re losing them. I think when students want to get married and have children, the workload is not consistent with them doing all these jobs. You can say a lot of the millennials have equal partners who share in the workload, but equal partnering doesn’t mean the husband can give birth to the child. There are still roles the women play and somebody has to do the job disproportionally in child caring. Workplaces have not yet learned how to provide the kind of support to allow women to have a life and make a living. This change has to happen if we want to retain and promote women.

Another challenge we face is class stratification. We want people who step off the ‘track’ to come back. So we’ve started a trial programme to enable this. Also, if we want the best, we have to draw from the entire population, and the only way to do it is make the workplace an extension of the person’s life. For example, opening a day care centre here on campus, so parents, especially women, can tend to their children whenever necessary. More companies have to do this if we want women to come into the workforce.

How have you succeeded in combining the incredibly demanding roles of mother and CEO?

First of all, I have a very supportive husband, which helps. Second, having an extended family willing to help with the kids made a huge difference. They put their lives on hold to help us raise the kids.

PepsiCo itself is a great place because of the ecosystem that supported me. For example, even the CEO who I succeeded, Steve Reinemund, helped me pick up the kids when my husband was stuck in traffic; he’d say: ‘I’ll go pick up one and you go pick up the other’.

I’m very grateful to this company, for what it gave me and for what I’ve been able to do for the next generation of employees.

What advice would you give students on how to start a career overseas or, given the buoyancy of India as a business superpower, are they better off staying in India?

India has many issues, and needs a strong group of leaders to take it to the next level. Brain drain from India is not a good thing but these students have many more opportunities today than existed when I graduated. In my class, I was only one of five women. Today, 20%-40% of the class are women. Things have changed, so it behoves those kids to give back to the country for what the country has invested in them.

India has its share of problems and these business students can do wonders to help the country address these issues. If an army of graduates from the country’s top business schools cannot solve India’s problems, who is going to?

They live in the midst of these problems, and they should sit down and figure out how to address them.

What do you believe is the best way to ensure lifelong learning?

Business schools have a unique opportunity. Let’s say I graduated today from Yale School of Management, I’d love Yale to say that if I pay another

X thousand dollars, I can come back for a refresher programme for the next X number of years, to learn about the most important and current topics and have access to their online education to go deeper in those topics.

It’s a golden opportunity to keep that connection with alumni, and because the world is changing so profoundly, it is not possible for leaders to keep up with everything that’s going on.

But today, we have to keep learning. For example, I grew up in a generation where social media didn’t exist, but I have to learn about it because the young people who work here, and who live on these devices, are the people generating all the noise. On the other hand, you can’t take a 30-year-old and say run a $63bn USD company.

I think each of us also has to do our own learning, figuring out our curriculum and how we need to engage certain topics, we can’t just wait for others to give it to us. For example, today’s CEOs have to be foreign policy experts, understand issues in every country and the role of multilateral organisations, how NGOs think and behave, and understand really deep sustainability issues.

We have to keep learning. Expertise is a leaders’ goal. But we have to strive for this goal.

How would you like to see business graduates make an impact on our planet?

I’d say to each of them, bring your whole self to work and think of what you’re doing as having an impact on your community. Make it very personal and see if the business is doing the right thing by the ecosystem in which you live in. If it isn’t, work in the company to change the model.

The young people who are graduating now should make their voices heard to create change. Through this, we can actually reform capitalism to be a real force for good.

This article originally appeared in the print edition (January 2019) of Business Impact, magazine of the Business Graduates Association (BGA).

Read more Business Impact articles related to corporate social responsibility:

Building a career with impact in CSR

Creative and ambitious people that can help businesses shape and deliver their CSR agendas are in demand, says Lakshmi Woodings. Discover what careers in CSR involve and the skills you’ll need to succeed

The principles of business ethics | How to adapt a responsible approach to management

As an impactful business school, adopting a responsible approach to business management is essential, for both the institution and its students alike. In this article,

The mutually beneficial pursuit of ethics and profits

Drawing on Apple and Patagonia as examples, The University of Law Business School’s Stuart Ailion considers the merits of strategies that combine ethical outlooks with profit making

Want your business school to feature in

Business Impact?

For questions about editorial opportunities, please contact:

Tim Banerjee Dhoul

Content Editor

Business Impact