Design thinking requires essential ‘front-end’ questioning skills to understand the end user’s experience fully writes David Steinberg

Allow me to introduce you to three hypothetical individuals, with differing priorities, who will set the context for the following article:

Zaha is a full-time MBA student at a prestigious Business School, taking a design-thinking course and learning how to apply the process to her capstone project. Her School will apply design thinking to help her take the next step in her career.

Anna is a partner at a prestigious consulting firm and responsible for recruitment planning. She recently completed a design-thinking course for executives offered by Zaha’s Business School. She’ll apply design thinking to help Business Schools around the world visualise the ideal student profile in three, five and even 10 years.

Etienne is Director of Post-Graduate Careers at Zaha’s Business School. He recently met and spoke at length with the professors who teach Zaha’s and Anna’s design-thinking courses. Etienne will apply design thinking to help his Business School align its curriculum to the strategic goals of the world’s most successful companies, including Anna’s firm. He’ll also help Zaha take that next big step in her career.

What Zaha, Anna and Etienne don’t realise is that their questioning skills are critical to the success of their design thinking.

Why? Because design thinking begins with empathy. With empathy, we can immerse ourselves in the world of the end user, and by doing so, we can properly frame the problem experienced by the end user, and go on to solve the problem together in extraordinary ways.

Design thinking fosters the co-creation of value, ideal for those who work in the highly competitive, ever-changing and relationship-dependent professions of graduate business career services and employer recruitment.

What is design thinking?

Tim Brown, CEO and President of IDEO, describes design thinking as ‘the integration of feeling, intuition and inspiration with rational and analytical thought.’

To Roger Martin, former Dean of the Rotman School of Management in Toronto, design thinking is a ‘balance between analytical mastery and intuitive originality’.

Meanwhile, David Kelley, founder of IDEO and the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford University, calls it a ‘framework that people can hang their creative confidence on,’ providing those who don’t consider themselves to be creative with a way to solve some of the world’s most complex problems.

University of Potsdam and Stanford University are two of the leading centres for the study and application of design thinking. Companies flock to the campuses to apply it to their challenges and change management. Ian Wylie at the Financial Times writes that industry adoption of design thinking ‘has encouraged Business Schools to add design-thinking methods to their executive MBAs and help students find innovative solutions in sectors from healthcare and pharmaceuticals to banking and insurance’.

It turns out that there isn’t one design-thinking process: several have emerged in the past decade, each with its own terminology and devotees.

For example, IDEO’s process focuses on inspiration, ideation and implementation. Roger Martin’s version requires ‘moving through a knowledge funnel’ from mystery to heuristic to algorithm. The Design Council, Google and IBM have their own versions. However, the Stanford five-step process is considered the gold standard: empathise, define, ideate, prototype and test.

Let’s bring in Anna and Etienne to help explain each phase of the Stanford process using a simple scenario.

Empathise: during a recent meeting, Etienne initiated a series of questions and learned some sobering news about new hires from his School. They’re not building trust with clients of Anna’s firm. Etienne then conducted extensive interviews with other clients and heard a similar story.

Define: Etienne returned to his School and met with faculty and staff to define the problem. They determined that the underlying issue was that students, while certainly high-calibre, lacked training in advanced interpersonal skills.

Ideate: Etienne’s team held a brainstorming session and came up with several solutions, including coaching and feedback, workplace simulations and field immersion.

Prototype: a sub-committee of Etienne’s team developed a prototype programme to solve the problem.

Test: Etienne’s School tested and tuned the programme with a selected group of graduate business students before formally launching it the following year.

The enduring value of the Stanford process is that when it is applied properly, it can produce innovative solutions that emerge not from the ‘ideate’ phase per se, but from the ‘empathise’ phase – the information-gathering phase. Proper application means not moving too quickly downstream into the latter phases – what most of us would consider to be the exciting bits involving late nights and whiteboards and lots of pacing around the room – without first understanding the underlying issues associated with the end user’s experience.

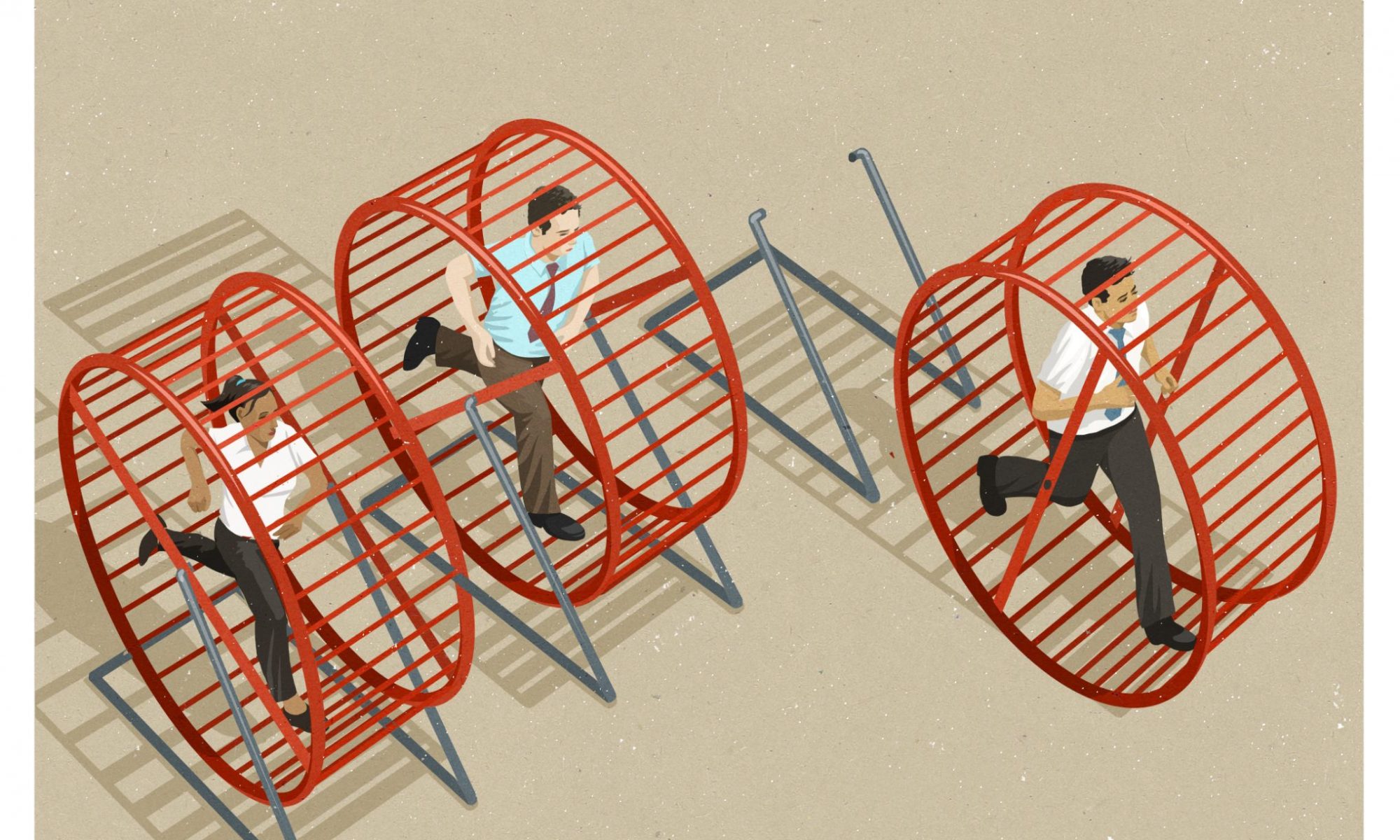

Here’s a common and costly mistake that many companies and organisations make: they conduct a few cursory interviews with end users; they think they understand the problem; they think they have a solution; they roll out the solution and go home feeling good. They return the next day… and the problem is still there.

IDEO’s Tim Brown describes empathy as the most important skill for the design thinker. He adds that empathic designers ‘notice things that others do not and use their insights to inspire innovation’.

Design thinkers are taught how to empathise by combining observation and engagement in ways resembling techniques used by ethnographers in the field. Observation includes looking for work arounds and for disconnects between what is said and what is done. Engagement means asking mostly ‘why’ questions to ‘uncover deeper meaning’.

If empathy is the most important skill for the design thinker, then asking questions comes a close second. However, there are as many generic approaches to understanding the end user’s experience as there are processes for design thinking. One size doesn’t always fit all. What follows is an approach to questioning tailor-made for the ‘empathise’ phase of the Stanford process and for people in career services and employer recruitment. Indeed, business students can also use it to complete their external projects. This approach will put you on the right path towards successfully defining and solving the end user’s problem.

Change points

Your first step as a designer is to determine the topics to explore with the end user. John Sawatsky, Michener-Award-winning investigative journalist and interview expert, argues that the secret to crafting compelling questions is to build them around ‘change points’, which are key changes in someone’s personal or professional life. In the context of design thinking, the designer seeks to discover change points in the end user’s experience and to understand the associated underlying issues. Focus on the timeframe before a change point and build your question sequence around it.

There are parallels between this process and an intriguing principle in Eastern philosophy called ‘ma’. According to theatre director Colleen Lanki: ‘Ma is a Japanese aesthetic principle meaning “emptiness” or “absence”. It is the space between objects, the silence between sounds, or the stillness between movements… The emptiness is, in fact, a palpable entity.’

Listen for ma in Japanese conversation in the form of question fragments, or in the silence between drum beats or flute notes or lyrics in Kabuki theatre. Look for ma in Japanese visual arts such as paintings that have empty space in them. Author and TV presenter James Fox notes that ma can give structure to the whole, the way open spaces in traditional Japanese homes are given meaning by those who live in them. It’s the spaces between the change points in people’s lives that offer rich insights for the design thinker.

Ask ‘what-how-why?’

Your next step is to develop a list of questions. In the early 1980s, Sawatsky began teaching journalism at various Canadian universities. He noticed that students who asked ‘what-how-why’ questions (topic-process-motivation) for class projects elicited more vivid responses from sources compared with students who used other words and sequences. This sequence corresponds with the neural basis of human listening.

Social Neuroscientist, Robert Spunt, at Caltech writes: ‘Listening requires not simply a comprehension of what others are saying and how they are saying it, but also why they are saying it: what caused them to say that and to say it in that way?’

Think of the what-how-why sequence as a navigational system in an aircraft cockpit. Use the sequence to prepare for your end-user engagement by developing questions that function as waypoints between the first and last topic you’d like to explore.

In between the what-how-why waypoints, probe and clarify responses using questions that you deem appropriate; open-ended questions work best, particularly when you want to explore matters of degree such as confidence, dedication, and success. When you’d like the person to confirm or deny a topic, ask a yes/no question, but it’s best to do so after you’ve explored a matter of degree. Moreover, use what-how-why when the person offers you a revelation. If you only have one opportunity to ask the person questions, you must quickly improvise a new sequence. You might eventually return to your original flight plan, or you might decide to stay on the new course. You’re the pilot.

Remember: we prepare to improvise.

PHASE 1: DEFINE THE CHALLENGE

The Stanford ‘empathise’ phase begins with defining the challenge. This can be interpreted as discovering one or more change points associated with the end user’s experience. Three question models follow to jumpstart your information-gathering process:

Etienne’s questions for Zaha

• What was a positive moment during your time at the Business School that you vividly remember and often reflect on?

• How did this moment make you feel?

• Why do you think this moment made you feel this way?

This question sequence helps Etienne ‘dig into the emotion’, as the Stanford design school phrases it, to help Zaha take the next step in her career. Etienne learns that Zaha often thinks about her idea for a startup project in her elective: to build high-definition cameras and install them inside incubators in neonatal units to help parents see their newborns when they’re away from the hospital. Her work group’s enthusiastic response to her idea gave her a level of confidence she’d never had before.

Etienne’s questions for Anna

• What is your firm’s top strategic goal in the next five years?

• How will this strategic goal change your firm?

• Why is this strategic goal important to your firm?

This sequence is designed to create alignment between Etienne’s Business School and Anna’s firm, while at the same time assuring that he understands the underlying issues associated with her firm’s strategic goals. Etienne learns that Anna’s firm has access to vast quantities of data with no means of harnessing it for clients. He also learns that the firm’s managing director is growing uneasy about the fierce competition from rival consulting firms, and has asked for ways to design innovative solutions for clients and to roll them out more quickly. Indeed, Etienne learns that the firm would like to launch a new data/predictive analytics division.

Anna’s questions for Etienne

• What, in your view, is the next step for our employer/ Business School partnership?

• How can we collaborate on this next step?

• Why do you feel this step is right at this time?

This sequence is also designed to align Etienne’s Business School with Anna’s firm but from Etienne’s perspective. Anna learns that Etienne’s Business School proposes to co-create the new analytics division to help the firm’s clients address their own customers’ challenges and make informed predictions about the future. Students would enrol in a new business immersion course and spend six weeks at Anna’s firm.

After the induction period, students would then work on challenging projects based on their specialisation. This partnership would provide students with the immersive learning experience they expect, and provide Anna’s firm with a continuous supply of ideas and skills provided by students at one of the world’s premier Business Schools.

PHASE 2: GATHER INSPIRATION

Once you have defined the challenge by discovering a change point, the next step in the Stanford ‘empathise’ phase is to gather inspiration, which can be interpreted as exploring the change point. Help the end user go deeper into their experience.

As market research interviewers will attest, the end user’s first response may not fully capture their feelings.

For example, the end user might initially describe their long-haul flight to Shanghai as being ‘fine’, but after a few probing questions, ‘fine’ turns out to mean ‘the in-flight meal was average and the entertainment was limited’.

Here are three ways to explore a change point:

Ask an immersive question

Craft a question in a comparative structure and turn up the contrast.

For example, Etienne might ask Zaha this question to learn more about how her work group’s positive reaction to her start-up idea has changed her self-perception: ‘Thinking back to your work group’s positive reaction to your startup idea, how would you compare your perception of yourself as an entrepreneur then and now?’

Embed a verbatim comment

Embed a verbatim comment made by the end user in a comparative structure and once again, turn up the contrast. For example, Anna might ask Etienne this devil of a question to learn more about his Business School’s vision of the ideal student profile in five years: ‘You recently said that “artificial intelligence will reshape labour markets in unimaginable ways”. How would a student’s profile that takes into account the rise of high-level machine intelligence compare with the profile of a current student?

Wrap the change point

Again, it’s the spaces between a change point that are as important as the moment of change. Ask one question that takes the person back into the moment before the change point. Ask a second question that explores the actual change point. Then ask a third question that explores the moment after the change point.

For example, Zaha might ask the following three questions to her client at Lego as part of her capstone project:

• Thinking back to 2012, before you introduced your co-creation process, how did Lego developers bring their ideas to market?

• When Lego introduced co-creation with customers, what were the steps to bring these products to market?

• What’s the primary difference between products created only by Lego developers and those co-created with your customers?

Design thinking offers people in career services and employer recruitment a way to co-create rather than dictate solutions. It also offers a way for students to hone their problem-solving skills and to co-create solutions with their clients for class projects.

However, design thinking requires essential ‘front-end’ questioning skills to fully understand the end user’s experience. Mastering these skills will assure that everyone involved is headed in the right direction.

Dr David Steinberg is Principal at Reykjavik Sky Consulting. He conducts MBA masterclasses on advanced questioning skills at several Business Schools including Cass Business School and Nottingham Business School and is Associate Professor in Leadership, Strategy and Organisation at Heriot-Watt University.